Sometimes your plans get disrupted. Sometimes you take a leap of faith.

That’s the story of David Sutherland.

He started as a musician.

“Years after I had finished a PhD in musicology at the University of Michigan and had taught for four years, I couldn’t get a job. And I decided, well, hey, teaching didn't work out so well," he said as he sat at a harpsichord he built.

It's been an interesting journey since.

When he was a teenager, he’d visited the shop of one of the better harpsichord makers in the world. His name was John Challis. He worked in Ypsilanti and later Detroit. Sutherland was hooked. He wanted to build harpsichords. His parents persuaded him that going to college made more sense.

So, he did. But, as we heard, teaching didn’t seem to be an option for Sutherland. He was married. He had a child. He decided to apprentice with a harpsichord maker, Frank Hubbard.

"It was a wildly irresponsible decision financially. I mean I just decided well, I'm going to do it. So I did it. And we somehow, somehow we got by. I don't know how and yeah I have never regretted it," he said

In his own shop, David Sutherland ended up making about 100 harpsichord and other keyboard instruments (see some of his harpsichords here), chiefly, Italian harpsichords which most musicians at the time didn’t seem all that interested.

“We all thought at that time well the Italian instruments are just these little dinky things. They, you know, they have very few notes and they only have one keyboard and so forth. And it took me a while to realize how, how wonderful the style was,” Sutherland said.

However, this was the beginning of interest of the 20th century's interest in 'early music.' Along with musicians studying the music of the Reinnasance and before, there was an interest in the instruments of the time, such as the Italian-style harpsichord.

So, that’s how he made his living for a long time. Until his interests changed. But, more about that later.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JNYmZ0EM5k&t

He kept his last harpsichord and it’s in his home.

David Sutherland: "I think that I made this about 2010."

Lester Graham: "So just a matter of losing interest in this particular instrument?"

DS: "I just got really interested in the pianos. The fact of the matter is that pianos are a lot closer to harpsichord than we realize."

The chief difference is in the mechanism of how the instrument plucks or strikes the strings.

There was an Italian musician working for the aritocratic Medici family of Florence. Bartolomeo Cristofori came up with a way to strike the strings of a keyboard instrument that allowed dynamic variation, soft and loud, which is what 'pianoforte' means.

So, we know who invented the piano.

"We don't know who he apprenticed with her where he worked with. But he was established as a keyboard instrument maker in Padua which is the university town of Venice sometime in the late 17th century. This is the late 1600s we're talking about. He got the idea of equipping these instruments with a much more precise and profound capacity of dynamic variation. And in particular being able to change from note to note so that you could play loudly and then softly and then loudly and then softly which you can't do on an instrument like this,” Sutherland exlpained.

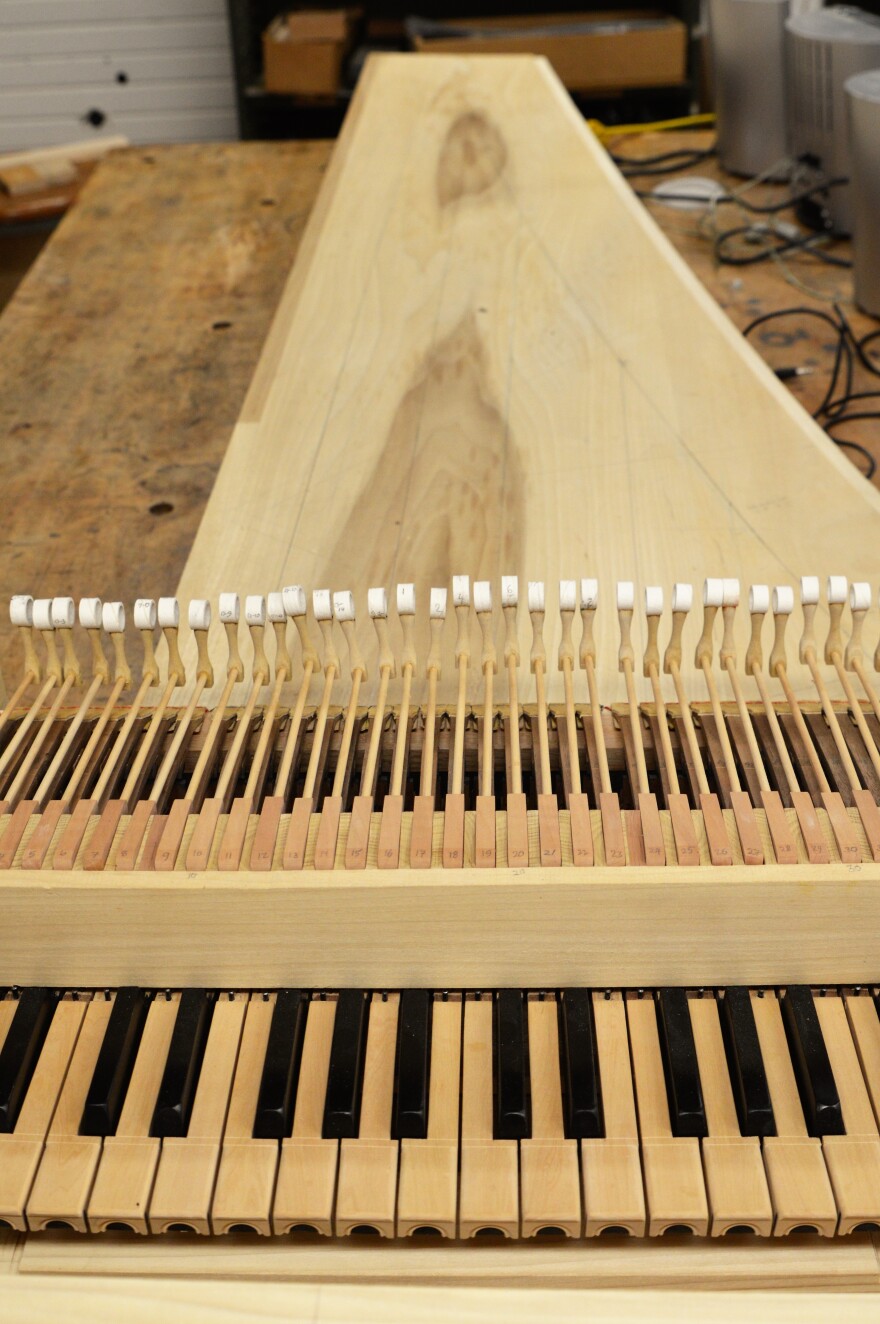

And so, that’s what he makes now: Replicas, copies of Cristofori’s pianos (see some of Sutherland's pianos here). He’s working on his sixth piano as he showed me in his shop.

LG: "This piano is not complete."

DS: "No."

LG: "But it looks very much like the shape and form of the harpsichord you were just showing me."

DS: "Yeah. Absolutely. I remember when I first I made my first piano and took it around showing it you know at various places. People would say me, “But it looks like a harpsichord,” and it really irritated me. I mean, I tried to be polite and say well it's not a harpsichord. It's very different. You know and I would say these dumb sh- it’s not a harpsichord, it’s a piano. But yes it looks exactly like and it was named by the same name. It was an improved string keyboard instrument."

Sutherland’s first piano actually got some interesting attention. He’d made one for the St. Paul Schubert Club in Minnesota. That was a couple of years before the Smithsonian’s American History Museum held a special exhibit on the 300th anniversary of the piano. The Smithsonian actually got one of the three remaining Cristofori pianos for the exhibit from the Italians. It was a hugely popular exhibit and the folks at the Smithsonian wanted to extend it.

DS: “So they got in touch with the Italian government and the Italians said, 'No dice. We want it back.' So then they thought, 'What are we gonna do?' So they finally wound up by writing to the Schubert Club in Minneapolis who had commissioned this and saying, 'Can we borrow this for the continuation of the piano show?'”

LG: "So, they borrowed your piano from the St. Paul Schubert Club?"

Sutherland nodded yes, then turned to a CD of performances on that piano.

DS: “The track on here that I'm suggesting would be good for this show gives a very interesting idea, I think a good idea, of what the piano was especially favored for the beginning which was its ability to play softly."

The track was Elaine Funaro playing a piece by Giovanni Benedetto Platti part of which you can hear in the audio at the top of this story.

LG: "How long have you been making harpsichords and pianos?"

DS: "Well the first, my first dated instrument was 1974 and then I retired in about three years ago."

LG: "You didn't retire. (laugh) You’ve got work right here on the bench."

DS: "I intended to [retire]. I'm not at the top of my game anymore. And it's really hard to do this I only I can only work about four or five hours during the day and I make mistakes and I'm- I just feel as if it's really hard to get myself together to do this because it's a very challenging instrument. It's very challenging instrument.”

David Sutherland hopes to have this piano finished by sometime this summer.

“I would like to make one more after this one. Another version another repetition of this pattern. I would really like to. And I would love it if the School of Music would buy it,” he said.

That is, the University of Michigan School of Music. He thinks there’s a pianist there who would appreciate a Cristofori piano in the same way he has appreciated making them.

That’s David Sutherland, maker of harpsichords and now pianos, our latest Artisan of Michigan.

Support for arts and culture coverage comes in part from the Michigan Council for the Arts and Cultural Affairs.