In some of the poorest neighborhoods in Grand Rapids, in places inured to academic failure, children are grasping at a chance to defy the odds.

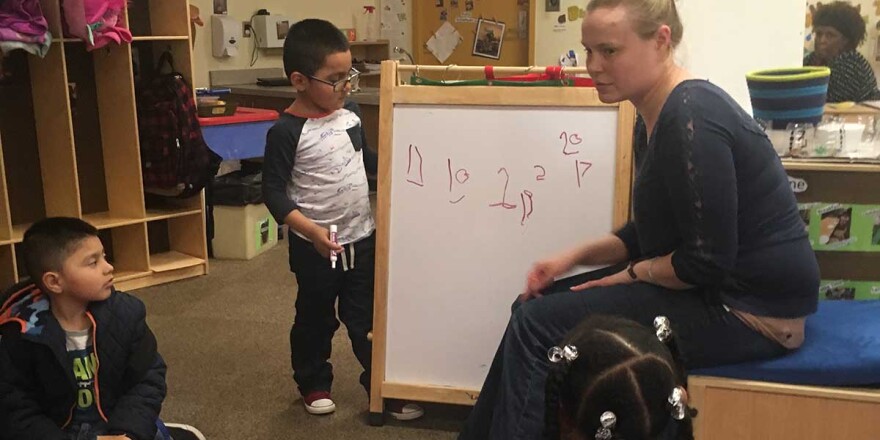

So it was one recent spring day, in a pre-K classroom on the city’s southwest side. In a poor, largely Hispanic neighborhood, where more than half of adults over age 25 lack a high school degree, a group 4-year-olds watched a classmate draw a “2” and a squiggly “0” on a whiteboard.

Their teacher, Sadie Kovich, asked: “What is it if the 2 is in front and a 0 is in back?”

After a pause, one of the kids, then a second, blurted out: “Twenty.”

Given the area’s demographics, it’s a promising glimmer of early learning. And one that’s being repeated in 34 classrooms scattered around the city, in a pre-K network that brings uncommon resources to bear for some 400 children and their families.

Classes are small. Teachers are well trained. Family coaches, often bilingual, help parents with everything from applying for cash assistance to figuring out how to get a car fixed to setting vocational goals. Just as important, teachers, coaches and administrators encourage parents at every step to share in their child’s learning.

The Early Learning Neighborhood Collaborative (ELNC), launched in 2011, it is now enrolling some children before they can walk, in a venture made possible by millions of dollars in foundation funding.

It appears to be getting results, even as it raises some inevitable questions:

Can early learning programs like this be expanded to help low-income students across Michigan?

Are state taxpayers willing to help fund universal preschool, knowing they won’t see financial benefits for many years?

“This is an investment,” said Tim Bartik, a senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, whose research has found long-term financial benefits to early education. “You are investing up front and you are receiving benefits over time.”

Failure no longer inevitable

In 2009, then-Grand Rapids Public Schools Superintendent Bernard Taylor noted that 83 percent of Grand Rapids students were not ready to enter kindergarten. The children, he said, were “not even at the starting gate.”

As recently as 2016-17, an assessment of 4-year-olds in the Grand Rapids program still found fewer than half met age expectations for learning and readiness when the preschool year began that fall. By spring, however, 90 percent or more met expectations. The program’s three-year-olds posted similar gains.

“This makes a tremendous impact,” said Dr. Nkechy Ezeh, founder and CEO of ELNC said of the program. “We know that the brain is ready to learn, really from 0 to 5. We have to strike while the iron is hot.”

Experts on Gov. Rick Snyder’s Michigan’s 21st Century Education Commission last year recommended universal preschool statewide as as critical part of reversing Michigan’s educational decline. But that hasn’t happened, by and large, because it would cost $400 million more per year.

Can the results emerging from Grand Rapids help change the tide in Lansing?

The Grand Rapids program is built around partnerships with several community nonprofit organizations, and learning strategies educators already know work.

But it was the Battle Creek-based W. K. Kellogg Foundation that laid the crucial foundation: giving $5 million in 2012 and $5.5 million in 2016. With a $1.95 million federal grant in 2017, ELNC this year added 12 classes for children under age 3, some as young as 3 months old.

It’s extraordinary spending for such a targeted program. But without the Kellogg investment, especially, ELNC would not exist at this level.

“We know this is important for the state,” said Kellogg Foundation program officer Yazeed Moore, who considers ELNC one of Kellogg’s “rockstar” success stories. [Disclosure: Kellogg is a funder of The Center for Michigan, which includes Bridge Magazine. The foundation played no role in the writing or editing of this article]

Moore said he is unaware of many Michigan communities that devote so many resources to pre-K education. “How do you begin to think about those resources, whether they are public or private, to support this kind of instruction?”

ELNC’s 4-year-old classrooms are funded through the state Great Start Readiness Program, a state-funded network of high-quality pre-K classes. Michigan added more than 21,000 kids and $130 million to its Great Start program after a 2012 Bridge Magazine investigation revealed that 30,000 eligible 4-year-olds weren’t enrolled because of lack of funding.

But Great Start is limited to 4-year-olds, a limitation ELNC seeks to break through by creating classes for 3-year-olds and younger.

John Austin, former president of the Michigan Board of Education, applauds the state for expanding access to Great Start. But the state acknowledges there are still roughly 30,000 4-year-olds from low- and moderate-income families without access to quality early education.

“There’s still a gap,” Austin said, noting other states, such as Oklahoma, where all 4-year-olds have free access to quality pre-K education, have invested more heavily in early learning.

Studies show high-quality early learning programs can help close the learning gap low-income children typically bring to kindergarten. That includes a 2016 study that tracked Kansas children from disadvantaged homes and compared those with access to high-quality early education to those who did not.

By fourth grade, the study found, the students with quality early education “scored significantly higher” on math and reading tests. They were also more likely to attend school, and faced fewer discipline referrals.

A more famous 2005 study found significant long-term benefits. It tracked more than a hundred students from low-income families in Ypsilanti and compared those who were enrolled in the 1960s in a quality preschool program with those with no preschool. By age 40, those who had been in preschool had higher incomes, were more likely to be high school graduates, own homes and have longer marriages.

Ezeh, the ELNC founder, is optimistic students in his program will see improved outcomes as they progress through school and beyond.

“I really do have high expectations,” Ezeh said, noting that without early intervention children from poor neighborhoods are far more likely to fail in school.

Students from households in the bottom fifth for income are more than four times more likely to dropout of high school than those from families in the top 20 percent. High school dropouts earn one-third less than high school graduates, about a third of what college graduates make and, according to one study, are 63 times more likely to be incarcerated than students who finish college.

Poor children start behind

Learning gaps between poor and more affluent children show up in toddlers as young as 18 months old.

A 2013 Stanford University study of California children found that 18-month-old children from wealthier homes could readily identify pictures such as “dog” or “ball” much faster than children from low-income households. Six months later, at age 2, children from wealthier homes had learned 30 percent more words than children from poor families.

Researchers say parents in wealthier homes are more likely to engage toddlers verbally and read to them more frequently. That makes early learning programs even more critical for the most vulnerable children.

In 2010, Kellogg foundation officials approached Ezeh, director of the Early Childhood Education Program at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, to research the educational needs of children in core areas of Grand Rapids. Ezeh found a majority of the 5,000 children in those neighborhoods had no access to quality pre-school.

It confirmed what former Grand Rapids Superintendent Taylor said: Most were losing the race by kindergarten.

The program is deliberately neighborhood focused, Ezeh said, and its classrooms reflect the culture of each neighborhood to make families and children feel welcome. In the school based in the predominantly Hispanic neighborhood, a play area includes small tortilla presses. A tablecloth features a print from Guatemala and pictures on the wall reflect Latin American countries that mirror the heritage of many students.

At an ELNC school on the southeast side, with a mix of African American and white households, family coach Denise Solomon sat down in a meeting room to explain her role.

Like other coaches, Solomon meets with the parents at the start of school to document their needs, and to begin building a relationship. She has dealt with parents who are suddenly homeless, without a job, depressed, or in some cases struggling to walk their child to school in the depths of winter.

She’s the problem solver. The goal: Do everything possible to maintain a stable home. “If they are not stable, the kids cannot learn,” Solomon said. “They come in out of control. They can’t concentrate. You can always tell when there is something going on at home.”

Research backs her up, as “toxic stresses” like domestic violence or drugs in the home interferes with learning and can have damaging effects. Another study concludes that “household chaos” is linked to greater likelihood of child misconduct.

This past winter, Solomon worked with a young mother with a 3-year-old in the program who can’t drive because of a seizure disorder. She walked him to school from more than a mile away, but began missing days when it snowed or rained.

Solomon found other families to pitch in with rides, and then, finally: “We got her a bus pass.”

In 2017, Nomsa Deng, 31, a mother of two, found herself depressed and with lingering pelvic pain following childbirth. She was in a divorce and struggling to afford clothing for her children. Her 4-year-old daughter, Zoey, is now in Solomon’s program.

Deng said there were days she could not drag herself out of the house to get Zoey to school. Solomon reached out.

“She found another parent close by to bring her to school,” Deng said.

At the ELNC school on the city’s southwest side, acting administrator Kim Spencer said the program’s relationship with parents is critical.

In March, students took home a calendar page and colored a box each day that a parent or sibling read to them at home. Many filled in every day, their family’s proud achievement put on display on the classroom wall. Spencer said the school encourages parental involvement throughout the year, with take-home projects a parent and child do together “so the parent understands the importance of educating their children.”

Tricia Jackson is in her fourth year as a “lead” teacher in the 4-year-old program, which, like that for 3-year-olds, has two teachers for every class of 16 students. Lead teachers must have a bachelor’s in early childhood education. Jackson has a master’s degree.

Perhaps more than academic progress, Jackson gauges readiness by a student’s social development. She sees students who begin the year shy and withdrawn but leave with the maturity to verbalize concepts, to solve differences with classmates with words instead of conflict, to concentrate and listen.

“Most could not write their names at the beginning of the year. They are writing their names now,” Jackson said.

“And when their parents tell me their child is eager and happy to come to school, that is my biggest reward.”