Jesse Buttrick Davis was born in Chicago in the year of the Great Fire of 1871. His father was a lumberman who died young.

His mother, whose lineage traced back to the Mayflower, eventually remarried, to a Baptist minister, and the family moved to Detroit where, in 1886, Davis went to Detroit High School.

He was a white man from a good family living at the end of the 19th century in America. Which means he had something very few people in the history of the world had ever had before him: a choice about his future.

And he had no idea how to make that choice.

“All the old ladies in father’s congregation assumed that I would follow father without asking my opinion,” Davis later wrote in a memoir. “One day during a church convention I escorted an old gentleman delegate who was staying at our house to the place of meeting. He was a kindly minister who seemed to take an interest in me. As we were walking along the street he said to me, 'Young man, what are you going to do with your life?'”

Davis knew in that moment he didn’t want to be a minister. Beyond that, he had no answer.

Going off to college didn’t seem to help. He went to Colgate University, passing through elms and willow trees, up a hill to the campus in upstate New York. It was a traditional liberal arts college. Davis trained in Greek and Latin.

“I was fairly well prepared to live in the Middle Ages,” Davis wrote. “I knew practically nothing of the century in which I lived nor of the workaday world into which I was soon to launch, labeled with a coveted degree and carrying a sheepskin diploma tied up with a white ribbon.”

The final semester of his senior year, Davis and his friends were looking for a class that would be an easy credit. They settled on one called “Pedagogy.”

“We were not sure what pedagogy meant,” Davis said. “The course turned out to be a history of the philosophy of education.”

That is how Jesse B. Davis ended up as an educator. And how, eventually, he became principal of Central High School in Grand Rapids, where he would help launch a new experiment in teaching. It was an experiment that quickly became a movement. And that movement transformed the entire purpose of education in America.

We are still living with the transformation today.

What are schools for?

It began for me as a question that became a sort of obsession.

We live in a time when nearly every preschooler can answer the question "What do you want to be when you grow up?"

I wanted to know why schools focus so much on jobs. Turning people into workers, it often seems, has become the main purpose of education.

We live in a time when nearly every preschooler can answer the question “What do you want to be when you grow up?” They know that the answer to the question must be a job. They learn young that their very being is defined by their job. Their entire school lives, from that first preschool class, to the final year of graduate school (if they make it that far) reinforces the idea.

Most educators put it in different terms. They’ll say they’re preparing kids for “success” or that schools are teaching 21st century skills.

But the goal is for the kid to grow up, and get a good paying job. Which is a good goal, but should it be the main goal, the main purpose of education? Jobs are important, but they aren’t everything.

I wondered how it got this way. Education leaders didn’t always talk about the purpose of education this way.

There’s an easy answer: The corporations and business have come to dominate so much of our lives, that of course they’d dominate our schools. But that answer strikes me as too easy, too simple. Even if it were true, it wouldn’t explain how the transformation happened.

So I started reading. I found hundreds of pages of speeches, reports and conference proceedings. I looked at archeological studies of ancient schools. I found the memoir of Jesse B. Davis. And I realized this story of how schools changed ran right through Grand Rapids, where I live. It played out at a high school building I drive past every day.

This is what I learned.

The “imperious duty”

Schools have been a part of human life for thousands of years.

The first mention of schools in ancient Egypt dates back to the 10th Dynasty, about 3,900 years ago.

At least 3,500 years ago, young people in ancient Sumer were sent to Edubas, or tablet houses, to learn how to become scribes. One poem, recovered from the broken fragments of dozens of clay tablets, describes life as a schoolboy:

“[W]ake me early in the morning, I must not be late, (or) my teacher will cane me," the student tells his parents. “When I awoke early in the morning, I faced my mother, and said to her: ‘Give me my lunch, I want to go to school.’ My mother gave me two ‘rolls,’ […] I went to school. In the tablet-house, the monitor said to me: ‘Why are you late?’ I was afraid, my heart beat fast.”

Even as early as 2000 B.C., parents could go overboard on the graduation parties.

The caning commences.

But the schoolboy continues his studies, and eventually learns how to become a scribe. His father is so proud, he pours out the “good oil” and dresses the schoolboy in new garments. Even as early as 2000 B.C., parents could go overboard on the graduation parties.

Schools weren’t always formalized, and they weren’t always for the elite. In both Africa and North America, educational systems existed before the arrival of European colonists. Incan and Aztec societies had universities, and some of the students of the Aztec calmecacs came from lower classes. Religious schools in the ancient Vedic culture on the Indian subcontinent were open to both boys and girls of various caste backgrounds.

But for thousands of years, that was the exception rather than the rule. The evidence is piled up across cultures throughout history, from the clay tablets in ancient Sumer, to oracle bones of the Shang dynasty in China, to Plato’s Republic and John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education.

For most of the history of humanity, the purpose of schools has been to train the ruling elite.

So it was in America as well. But the nation that believed it was ruled by its citizens had to have schools to train those citizens to rule. The European colonists to the continent set up their first schools as early as the 1600s. At first, they were religious schools created by the Puritans. But after the revolution, leaders of the new nation imagined a new kind of school.

The Constitution of Massachusetts, signed in 1780, specifically called for the support of public schools, “for the promotion of agriculture, arts, sciences, commerce, trades, manufactures, and a natural history of the country; to countenance and inculcate the principles of humanity and general benevolence, public and private charity, industry and frugality, honesty and punctuality in their dealings; sincerity, and good humor, and all social affections and generous sentiments, among the people.”

Thomas Jefferson introduced "A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge" in the Virginia legislature to establish public schools there.

These schools were not actually universal schools, of course. A nation governed by white men created schools mostly for white men. While many of the public schools were open to both boys and girls, it was only the boys who could advance to college. Both William & Mary in Virgina, and Harvard in Massachusetts didn’t admit female students until the 20th century. After the Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia, the state passed a law that made it illegal to teach slaves to read. The native peoples of the continent did have access to schools, but the explicit purpose of those schools was assimilation. Students were separated from their parents and sent to boarding schools, where they’d be punished for speaking their native languages. “Kill the Indian … save the man,” the saying went.

But for the white kids, public schools had a different purpose. The schools existed to prepare them to be the rulers of their own government.

“In a republican government, legislators are a mirror reflecting the moral countenance of their constitituents,” said education pioneer Horace Mann, in an address to the Massachusetts legislature in 1848. “And hence it is, that the establishment of a republican government, without well-appointed and efficient means for the universal education of the people, is the most rash and fool-hardy experiment ever tried by man.”

This philosophy is what drove the idea of public schools across America, state by state. It’s true that religion played a major role in schools, even until the time of Horace Mann. But by the 19th century, that religious purpose fully gave way to a democratic one.

The 1835 Constitution of Michigan called for common schools, and called for the legislature to “encourage by all suitable means, the promotion of Intellectual, Scientifical and Agricultural improvement.”

In 1836, Michigan’s first governor, Stevens T. Mason, addressed a joint session of the state legislature and spelled out what the purpose of education should be for the young state.

“Public opinion directs the course which our government pursues,” Mason told them, “and so long as the people are enlightened, that direction will never be mistaken. It becomes then your imperious duty, to secure to the state, a general diffusion of knowledge.”

When a resident of Kalamazoo challenged the legal authority of the village to levy taxes to pay for a high school, the Michigan Supreme Court in 1874 ruled on the side of the district.

A free, public school system in Michigan, and in the United States, was firmly established. Its purpose was clear: Train the people to rule themselves and preserve Democracy.

But by the end of the century, schools were called to a new purpose.

Minds and machines.

The problem was work.

Millions of Americans barely had enough money to pay for food. Families had to work to scrape by. And the factories, fields and mines of the growing nation still needed workers. So parents sent their kids to earn a wage.

By 1904, about 20% of kids between the age of 10 and 15 worked, according to a New York Times report from that year. It was a crisis that provoked a national response.

A new organization, the National Child Labor Committee, formed in New York to tackle the problem. Its leaders knew that they couldn’t stop child labor just by outlawing it. Shady factory owners would still try to hire kids. Poor parents in need of extra income would still send them to work. And, even if new child labor laws banned it, inspectors would struggle to keep up with the violators.

What Committee members wanted, of course, was for the kids to go to school. So, as they worked to ban child labor, they also fought for laws that would force parents to send their kids to school.

“It is not enough to shut the children out of the factory,” said Felix Adler, the chairman of the National Child Labor Committee at the group’s first annual meeting. “We must also bring them into the school, and compel parents, if necessary, to send them to school. The movement for compulsory education everywhere goes hand in hand, and must go hand in hand, with the child labor movement.”

To sell both parents and business owners in local communities on the importance of schools, the reformers also came up with a new pitch: Send the kids to the schools, and the schools will make them better workers in the end.

“[B]ecause we recognize the significance and power of contemporary industrialism that we hold it an obligation to protect children from premature participation in its mighty operations,” said famed social worker Jane Addams at the meeting of the NCLC in 1905, “not only that they may secure the training and fibre which will later make that participation effective, but that their minds may finally take possession of the machines which they will guide and feed.”

If the original idea was to build public schools to train good citizens, the new idea became to support public schools to train good workers.

This is where Jesse B. Davis, and the experiment in Grand Rapids came in.

“Systematic guidance”

Davis arrived in Grand Rapids in the summer of 1907. He’d been hired to step in as the new principal at Central High School. The previous principal, Albert J. Volland, died suddenly at the end of the previous school year.

At the time, Grand Rapids was a booming factory town. The city skyline, long ago dominated by hardwood trees – oak, maple, beech – had ceded first to church steeples and then to smokestacks that dotted the downtown, spewing smoke that hung on the horizon, clouding the view. Buildings downtown became covered in thick layers of black soot.

But Central High School drew its students from the city’s elite, who lived in the hilltop area, now known as Heritage Hill, where the mansions rose above the soot and the streets were lined with trees.

Davis was still relatively young – in his 30s – but he’d been a teacher in Detroit for several years before coming to Grand Rapids. And he’d never forgotten his own struggles with choosing a career. He believed he could use his position at Central High School to try to give students something he’d never had – an education about the world of work.

“Here I was in a position to organize an entire school for systematic guidance,” Davis later wrote.

Almost immediately, he faced skepticism.

“When I first came to Grand Rapids, a large group of men meeting on Sunday mornings in one of the downtown churches asked me to address them on the subject of the guidance of youth and to tell what we were doing in the schools,” Davis wrote. “During the discussion period that followed my talk, a prominent furniture manufacturer took the opportunity to condemn the high school and its product. He was the typical “self-made” kind, proud of his handiwork. He claimed that for thirty years he had been employing high school boys and that he had never found one that was any good.”

Davis says he then asked the man a series of questions, and got him to admit that he couldn’t prove any of the kids had actually gone to high school. The man promised he’d contact Davis in the future before hiring anyone who claimed to go to Central High School.

“A few weeks later this same man sent me a letter of application from a boy who claimed to be a high school graduate,” Davis said. “The letter was beautifully penned but very faulty in grammar and expression. His name was not found in the records of our school; so I wrote to the boy asking for an interview. He came and admitted that he had never attended any high school … The employer did not hire this boy, but became a loyal supporter of the guidance program at the high school.”

This story isn’t the only example of how the schools in Grand Rapids came to be focused on the needs of the city’s growing business community. One of the prominent members of the school board at the time was George A. Davis (he was not related to Jesse B. Davis), who was also the head of a furniture manufacturing company.

Other leaders in the city had worked for years to get more technical training in the schools, to prepare students for their future work in the Furniture City.

Their efforts are documented in the book, The Failed Promise of the American High School, 1890 – 1995. The book makes the case that Grand Rapids is a “particularly good site” from which to understand the transition to more practical education system based on training kids for jobs.

“One of the first challenges facing the educational reformers in Grand Rapids was convincing an obviously skeptical public that the new, practical programs were the best examples of modern democratic education and that these programs advanced the cause of educational equality,” write the authors, David L. Angus and Jeffrey E. Mirel.

The city’s educational leaders argued 95% of the public school students didn’t go on to college. They wanted schools to give more “manual training.” So, in the Spring of 1904, they asked the voters to approve a new bond to pay for new equipment, and a new school. Voters turned it down. Later that year, the bond proposal went on the ballot again, and voters turned it down a second time.

Then the bond proposal to fund manual training went on the ballot again, for a third time. This time, the proposal got the endorsement of the mayor, Civic Club, Board of Trade, and four of the city’s leading newspapers.

“Despite all these endorsements, the proposal once again went down to defeat,” write Angus and Mirel. “All three of the elections divided along class lines – the wealthier wards and precincts strongly supporting the proposals, while the poorer wards, especially the middle- and working-class wards on the west side of the city, generally opposed them.”

It was the middle and working class families who were meant to benefit from the practical training in industry. But they didn’t want it.

Still, the city’s elites didn’t give up. After failing with the voters and with the school board, they took their case to Lansing. They were able to get a law passed to change how school board members were elected. The old, ward-based system was tossed out. School board members would be voted on city-wide, instead of representing individual neighborhoods. That meant the working-class West side wouldn’t automatically have a seat at the table.

The new board was elected in 1906. They hired Jesse B. Davis in 1907. And by 1911, they had a new high school building, four floors tall and nearly a block long, in red brick with gothic arches and sculpted gargoyles, all of it overlooking the elite, leafy hilltop neighborhood, where the building still stands today.

"Grand Rapids became a national model for vocational guidance"

An education in work.

The first thing they taught the students was ambition.

“The attempt was to arouse the desire to be someone worth while,” Davis wrote.

Students learned about ambition in their English classes. Reading and writing assignments were chosen based on the vocational theme Davis and his teachers selected. Ambition was the theme for the first year.

“The second year was devoted to the ‘World’s Work,’" Davis wrote. “Pupils reported on some occupation in which they were interested […] the third year’s guidance was the 'Choice of a Vocation, and Preparing for It.' In the last year, or twelfth grade, the emphasis was 'Service,' or the use of one’s vocation as a loyal citizen serving his community.”

There were shop classes, and sewing classes and cooking classes at the new high school. But Davis’ idea of “vocational guidance” went far beyond what we think of today when we hear of vocational education. It wasn’t a set of classes. It was an entire way of teaching, in all the classes.

“The spirit of guidance soon spread to all subjects in the curriculum,” he wrote. “The ‘career motive’ was used by all teachers to inspire a new interest in their fields of study.”

Soon, the experiment at Central High School was gaining interest nationwide.

“Grand Rapids became a national model for vocational guidance,” write Angus and Mirel, “a program designed to help young people match their interests to future jobs.”

Other educators began to take interest in the idea of vocational education. A national organization took shape. It was called the National Vocational Guidance Association. The group held its foundational meeting in Grand Rapids in October of 1913.

"Nothing can be more essential to the training of a child than a conception of his industrial obligations and opportunities"

“EDUCATIONAL WORLD WILL HAVE EYES ON GRAND RAPIDS” declared The Grand Rapids Sunday Herald. “Grand Rapids will occupy a foremost position in the eyes of the educational world this week and the conferences […] will be of interest to every city in the United States where modern methods in education prevail.”

One of the keynote talks was given by Owen R. Lovejoy, who served at that time as the head of the National Child Labor Committee.

“Nothing can be more essential to the training of a child than a conception of his industrial obligations and opportunities,” Lovejoy said. “I should like to have the entire curriculum shot through and through with the meaning, the history, the possibilities of vocation.”

For Davis, this became the mission. After the founding of the National Vocational Guidance Association, Davis wrote a book that outlined the curriculum used at Central High School. He traveled the country giving lectures everywhere he could to spread the word to other educators.

It worked.

“It went through several editions and was on the market for twenty years,” Davis said of his book. “It served a missionary purpose and that is a sufficient reward for the labor involved.”

At the end of his career, after he’d moved away from Grand Rapids and eventually become dean of the School of Education at Boston University, Davis reflected back on his work at Central High School.

“The pioneer work done in Grand Rapids undoubtedly pointed the way for much that has followed,” he wrote.

Learning to be our jobs.

Today, even in Grand Rapids, very few people know about the role of Central High School in transforming American education.

When my colleague, Bryce Huffman, asked teachers and administrators at the school today whether they've heard of Davis, most said they hadn't.

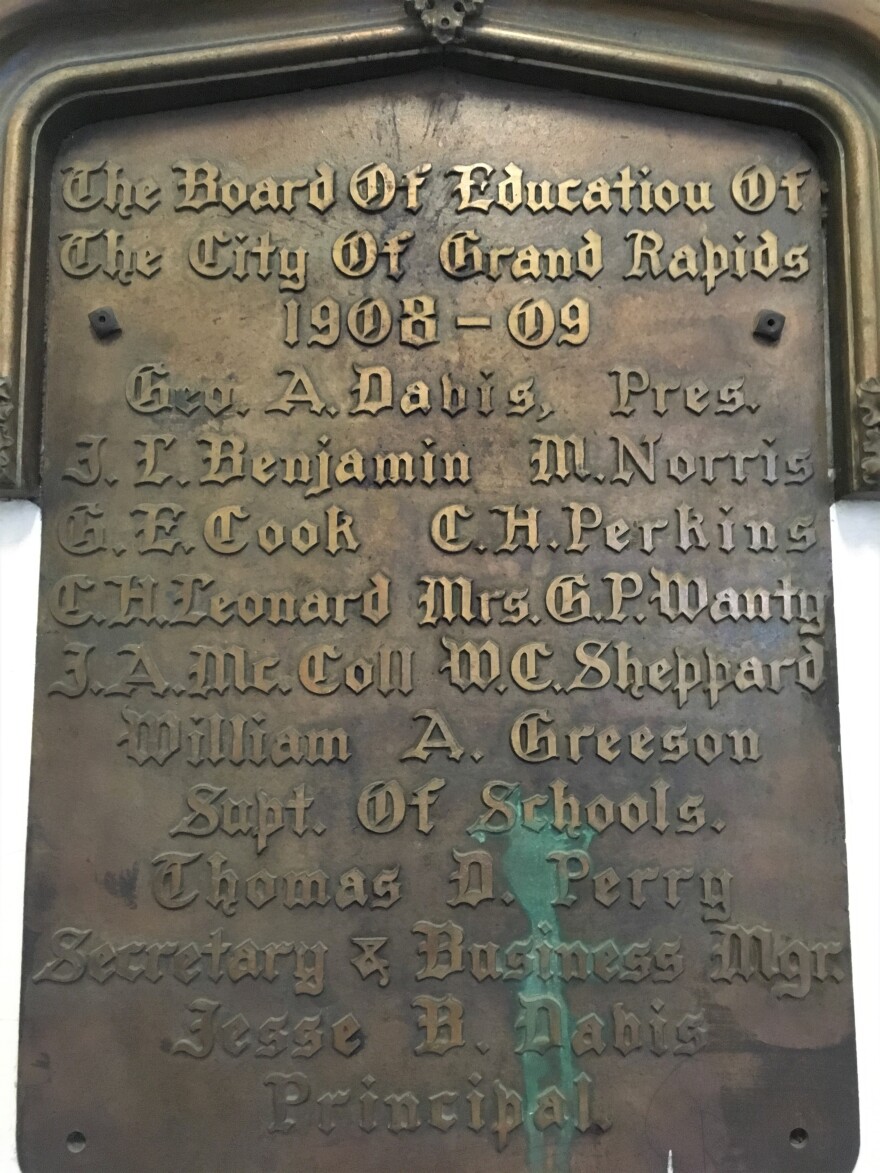

"I see his name," said the school's current principal, Mark Frost. "His name's down here on these plaques."

The school building today is known as Innovation Central. The entire curriculum is based on preparing kids for a vocation after high school. Just as it was more than a century ago.

Vocational education is still talked about as one branch of education. But that's not the only way the "career motive" enters into schools. Jobs have become the central purpose of nearly all schools.

“We believe that it is important to have a high quality education if one is going to succeed in the 21st century,” said George W. Bush, in his final policy speech as president, in 2009. “It’s no longer acceptable to be cranking people out of the school system and saying, okay just go – you know, you can make a living just through manual labor alone.”

Bush gave this speech to celebrate and promote one of the most important pieces of legislation he passed in his presidency, the No Child Left Behind Act. This was the law that mandated standardized tests nationwide for all students.

Tests are a way to measure learning. But they’re also important because test results have been correlated with earnings later in life. The better kids do on tests, the better job they’ll be able to get when they’re older, or so the logic goes.

There’s been plenty of pushback on testing in schools, but there’s hardly any disagreement on the underlying goal that the tests are meant to serve. You can challenge the tests, but you can’t challenge the idea that schools must prepare kids for jobs.

When the jobs market changes, schools have to change too.

“We live in a global economy,” said Barack Obama, in a speech he gave to high school students near the end of his own presidency. “And when you graduate, you’re no longer going to be competing just with somebody here in D.C. for a great job. You’re competing with somebody on the other side of the world, in China or in India, because jobs can go wherever they want because of the Internet and because of technology. And the best jobs are going to go to the people who are best educated.”

"Indeed, education and the economy are indivisible," says U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

“Indeed, education and the economy are indivisible,” said the current education secretary, Betsy Devos, in a speech last year to the International Congress on Vocational & Professional Training. “So students must be prepared to anticipate and adapt. They need to acquire and master broadly transferrable and versatile educational competencies like critical thinking. Collaboration. Communication. Creativity. Cultural intelligence.”

Statements like these from politicians and education leaders are so common, and so unchallenged, they mostly go unnoticed. People have to have jobs, so of course schools must prepare kids for jobs. That is The Way Things Are.

And if the purpose of schools is to prepare kids for a job, students have learned that their purpose is to have a job.

But the consequences of this reality are starting to surface.

“The idea that underlies contemporary schooling is that grades, eventually, turn into money, into choice, or what social scientists sometimes call ‘better life outcomes,’” writes Malcolm Harris in his 2017 book, Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millenials.

“By every metric, this generation is the most educated in American history,” Harris adds, “yet Millenials are worse off economically than their parents, grandparents, and even great-grandparents. Every authority from moms to presidents told Millenials to accumulate as much human capital as we could, and we did, but the market hasn’t held up its side of the bargain.”

The result, for an increasing number of Americans – Millenials included – has been anxiety, stress and burnout.

“Why am I burned out?” asks the writer Anne Helen Peterson in a Buzzfeed essay from earlier this year. “Because I’ve internalized the idea that I should be working all the time. Why have I internalized that idea? Because everything and everyone in my life has reinforced it – explicitly and implicitly – since I was young.”

Derek Thompson, of The Atlantic, says the problem isn’t just one of the Millennial generation. Many Americans now treat work as their identity, and pursue it as a kind of religion.

“A culture that worships the pursuit of extreme success will likely produce some of it,” Thompson writes. “But extreme success is a falsifiable god, which rejects the vast majority of its worshippers. Our jobs were never meant to shoulder the burdens of a faith, and they are buckling under the weight.”

The education reformers of a century ago never envisioned this outcome. They saw a rapidly industrializing society chewing up childhoods, forcing kids into hard labor, and they saw schools as the way to protect against it.

Jesse B. Davis wanted to ensure none of his students faced the crisis he did, of having knowledge, but no idea where to put it in the world. His ideas succeeded far more thoroughly than he ever knew.

But times change, just as the purpose of education has changed.

If the original purpose of the American education system was to train its people to be the wise rulers of democracy – to promote prosperity, freedom and self-determination through the pursuit of knowledge – what should the purpose be today? What is our “imperious duty?”

Is it still to prepare kids to become workers? Or is there another purpose waiting to be discovered?