One of the biggest pollution cleanup efforts in the Great Lakes region is getting a boost. The pace of repairing the damage in the most toxic hot spots of the region is going to speed up dramatically.

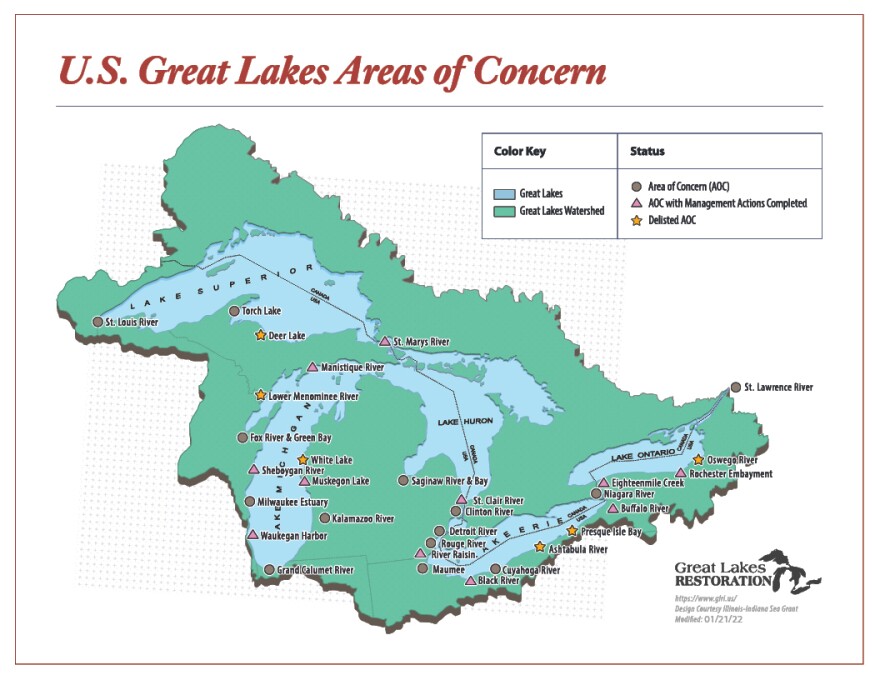

Back in the 1980s, the U.S. and Canada identified 43 highly polluted sites around the Great Lakes. The governments came up with a very government-sounding label for them: Areas of Concern. And then, not a lot happened.

“There was a slow burn, if anything at all, for many years,” said Mike Shriberg, executive director of the National Wildlife Federation's Great Lakes Regional Center.

He said not a lot got done until a new U.S. funding project under the Obama administration got bipartisan approval.

“And the GLRI, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, it accelerated things very much. If you look at the graph, it was largely flat before that. When the GLRI comes into being, you start seeing major progress.”

For the last eleven years, of the well over $3 billion in Great Lakes Restoration Initiative money, it has distributed about $1billion dollars to clean up Areas of Concern. That funding is continuing at about the same rate. But, there’s even more money getting added to that sum over the next five years.

“With one billion dollars in funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, combined with funds from the annual Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, appropriations, and funding from other sources, we projected by the end of the decade, we will have completed work at 22 of the 25 remaining Areas of Concern,” said Debra Shore, Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 5 and Great Lakes National Program Office.

That’s important to Michigan because of the 43 Areas of Concern, or AOCs, in Canada and the U.S., 14 — nearly a third of them — are in Michigan. So far, only three in Michigan have been completely cleaned up.

“EPA's goal for the management work to be completed on all but three AOCs in the U.S. by the end of this decade is absolutely bold, and I also find it quite inspiring,” said Liesl Clark, Director of Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE).

There’s one catch: Of those three that won’t be completely cleaned up, two are in Michigan.

Rick Hobrla is the EGLE state coordinator for the Areas of Concern program. Speaking to an Areas of Concern conference held in Michigan last week, he outlined why those two sites in Michigan would take longer to clean up.

The first one is the Kalamazoo River. In the past, there were a lot of paper mills in the area which produced toxic PCB wastes. Over the years, a series of dams was built, and behind each one PCB-contaminated sediment has piled up.

That cleanup is under Superfund, a federal program that is very involved and always lengthy.

A couple of the dams have been removed and the PCBs cleaned up.

Hobrla said two or three more might need to be removed, “But we can't just go in and remove the dams without having a comprehensive plan to handle the PCBs that are behind them. So we continue to work with the Superfund program on trying to move that forward.”

The second Michigan AOC that won’t be cleaned up by the end of the decade is the Saginaw River watershed and Saginaw Bay. Hobrla said the biggest problem there is nutrient enrichment — phosphorus and nitrogen runoff primarily from the surrounding farmland in the watershed. Since work began, things have been in flux.

“There have been huge food web changes in the Saginaw Bay over the time that — just over the time it became an AOC. We had a lot of fisheries goals that were set early in this century that we've had to completely throw out the window because the food web in Saginaw Bay now looks nothing at all like it did 20 years ago. It's completely changed,” he said.

The EPA projects those two sites might not be completely cleaned up until 2036 or beyond.

Environmental advocates such as Mike Shriberg at the National Wildlife Federation say that’s daunting, but the additional one billion dollars over the next five years will go a long way in completing the cleanup of the U.S. Areas of Concern.

“What I’m excited about is not only the clean up that’s happening, but think about this: When we have actually removed that toxic legacy, when we've actually rehabbed those sites, that actually should free up resources over the long term for other projects.”

He said seeing the Great Lakes region turn away from its history of industrial pollution and toward making waterfronts a point of community pride is heartwarming. But, after that, he said, seeing the continued Great Lakes Restoration Initiative funding spent on habitat restoration, building trails, and preventing invasive species damage, the next generation of benefits for the Great Lakes looks even better.

Clarification: This post has been updated to clarify that the total money distributed by the GLRI over the years has been well over $3 billion with about $1 billion going to AOC sites.