Bats with white-nose syndrome have been found in Mackinac and Dickinson counties in the Upper Peninsula and Alpena County in northern lower Michigan.

The fungal disease has killed more than six million bats in 27 states and five Canadian provinces since 2006.

Allen Kurta is a biology professor at Eastern Michigan University. He’s one of the researchers who found the infected bats. I spoke with him for today's Environment Report (you can hear him talk about white-nose syndrome above).

Kurta compares the discovery of white-nose syndrome in Michigan bats to "every member of your extended family receiving a terminal diagnosis."

“I think that this is one of the worst wildlife calamities ever in the history of North America. You’re looking at potential extinction of multiple species of bats.”

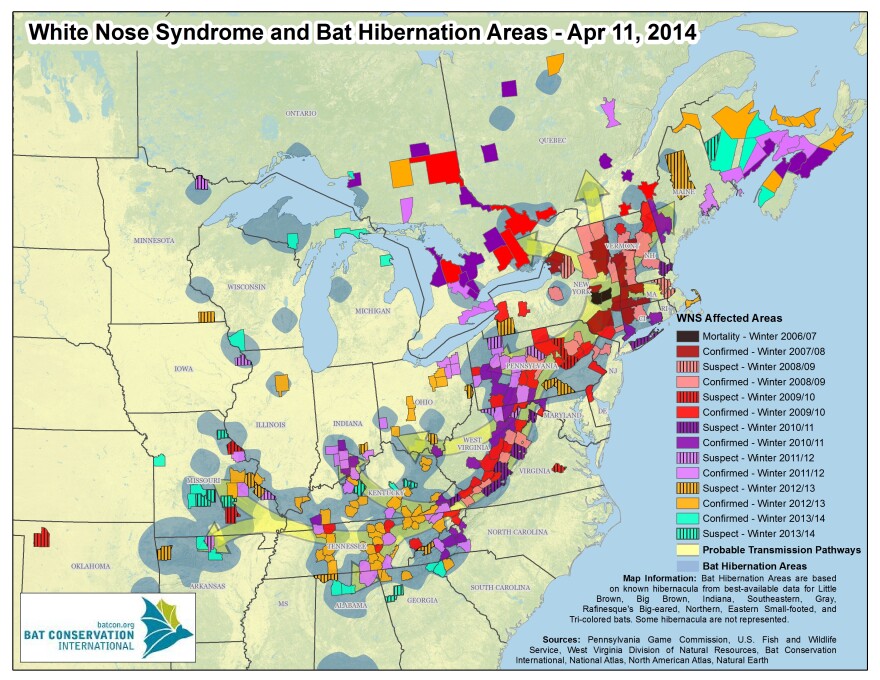

Here's a map of where white-nose syndrome has been found:

This February and March, Kurta and his colleague found five little brown bats with symptoms of the disease.

“The very first one, it was not really obvious and we relied on a strange characteristic that the infected skin will glow yellowish-orange underneath an ultraviolet light and that’s the reason we took that animal as a sample and had it tested; then it came back positive for the DNA and positive for what’s called histopathology, which is looking at the skin for the characteristic lesions that the fungus causes. The other two sites, though, when we went into them, it was very obvious, this characteristic tuft of white fuzz around the nostrils is distinctive and we did see that as soon as we walked into two of the sites.”

Burning too much energy

He says the fungus attacks the bats' skin.

“In the long run, what occurs is that they arouse from hibernation more frequently. That attacking of the skin probably is leading to increased water loss from the animal’s body, and they’re arousing from hibernation more frequently to replenish that water," he explains.

Kurta says normally, a bat will arouse about every two weeks from hibernation.

"The infected bats are arousing about once every seven days. That doubling of the number of arousals throughout winter costs a large amount of energy, a large amount of the fat they stored. So, by arousing much more frequently, they’re using up their fat much more frequently; they are then running out of that fat come February and March, and essentially they will die of starvation because there are no flying insects out there to give them food.”

He says there's nothing anyone can do at this point to keep the bats from spreading white-nose syndrome to each other.

“We do try to control spread from human sources by requesting that people refrain from going into underground sites and accumulating the spores on their clothing or gear and transporting it to another underground site. So we do request that and if people do go in, such as myself, a researcher, there are procedures we have to follow in order to kill the fungus if it happens to be present on anything we take into a mine.”

What about in our own backyards?

Kurta says you can put up bat houses, and you can be nice to the bats that happen to live in your own house.

"Anything we can do to make the lives of the bats easier probably is going to mean that more of them are going to survive. But we’re still going to be faced with the fact that 90% of them probably are going to die. The 90% of those that hibernate underground and that’s five of our nine species."

Federal and state agencies and wildlife groups have formed a partnership to coordinate a national response. Here's what they recommend if you want to help:

Avoid possible spread of WNS by humans Stay out of caves and mines where bats are known – or suspected – to hibernate (hibernacula) in all states. Honor cave closures and gated caves. Take a look at "Human Spread of White-Nose Syndrome: Why Decontamination is Important" poster. Take a look at For Cavers on the Service’s website. Avoid disturbing bats Stay out of all hibernacula when bats are hibernating (winter). Be observant Report unusual bat behavior to your state natural resource agency, including bats flying during the day when they should be hibernating (December through March) and bats roosting in sunlight on the outside of structures. More difficult to discern is unusual behavior when bats are not hibernating (April through September); however, bats roosting in the sunlight or flying in the middle of the day would be unusual. Bats unable to fly or struggling to get off the ground would also be unusual. Take care of bats Minimize disturbance to natural bat habitats around your home (e.g., minimize outdoor lighting, minimize tree clearing, protect streams and wetlands). Construct homes for bats (see below for directions). If bats are in your home and you don't want them there, work with your local natural resource agency to exclude or remove them without hurting them after the end of the maternity season (see below for more information). The best time to exclude bats is when they aren’t in your home.

And here are a few more things we can consider from Danielle Todd of the group Organization for Bat Conservation:

- Consider bats when planting your garden: plant native, night-blooming plants that will attract nighttime insects and eliminate the use of pesticides

- Become aware of local habitat issues including forest and wetland protection

- Invest in research being done to find a cure for WNS. The Organization for Bat Conservation's WNS Research Fund grants 100% of monies donated to the fund directly to researchers. Acting as an intermediary, OBC is able to direct donations to researchers who are unable to accept funds from the public. Link to fund: http://bit.ly/1t76A6f

a list given to us by Bat Conservation International has more information on how to build a bat house.

*This post has been updated.