When I arrive at Bethany Hawkins' home, the first thing she does is offer me a glass of her well water.

"Our water's always been really good," she says.

But Hawkins’ well could have an expiration date. It’s an estimated 675 feet from the edge of a plume of polluted groundwater.

A toxic legacy

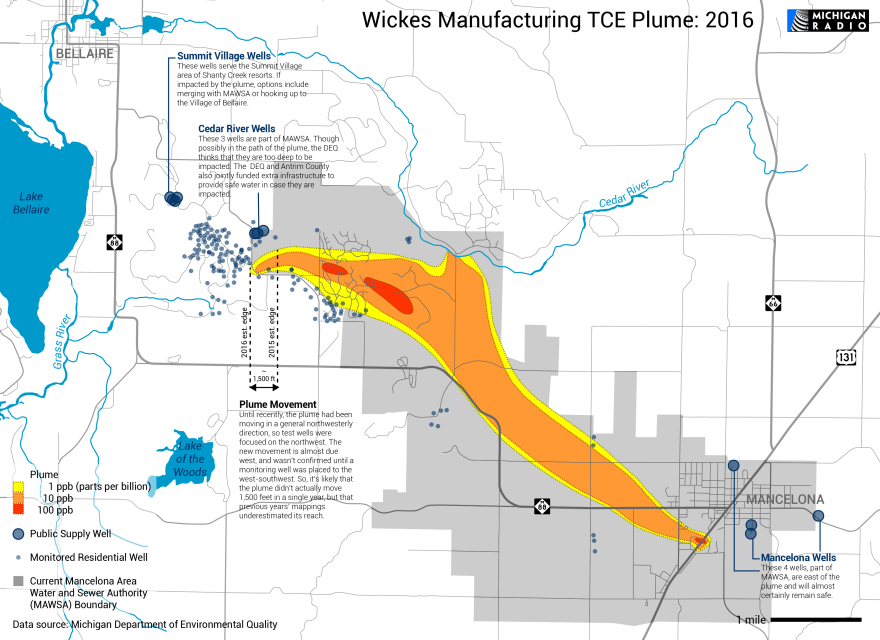

There's an estimated 13 trillion gallons of groundwater laced with TCE, or trichloroethylene, stretching from the village of Mancelona 6 miles away to the edge of Hawkins’ gated community.

(Subscribe to The Environment Report podcast on iTunes, Google Play, or with this RSS link)

TCE is a known carcinogen that can also affect the liver, the kidneys, the immune system and the central nervous system. The plume is the legacy of an auto parts manufacturing plant that stored TCE-containing degreaser waste in unlined pits.

Hawkins and her husband bought this house in the northern Michigan resort area of Shanty Creek back in 2004. At the time, they knew about the TCE plume. But they chose their home because they thought it would be out of the plume's path. But now...

"At this point there's nothing really to be done about it. It's going to hit us," she tells me.

The contamination has expanded more than a mile towards Hawkins' community since 2005, the year after she purchased her home.

Some unexpected movement

One section of it has recently taken an unexpected turn to the west, and might be moving more quickly than previously predicted -- the section by Hawkins' house.

Janice Adams is a senior geologist with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

“This one little narrow area that seems to be going very quickly, and must be, you know, it's very sandy and gravelly and it just seems to like to go through that better than it does the silt and the clay,” she says.

The DEQ has installed more test wells to monitor the plume’s progress in that direction. The engineering firm hired by the state to map the plume, Amec Foster Wheeler, told me it’s possible that the plume’s westerly movement is not new, just that previous years’ mappings underestimated its reach.

The health department alters its policy early

In any case, the local health department just extended the area of its “well first” policy five years sooner than it had expected to.

Scott Kendzierski is the Director of Environmental Health Services at the Northwest Michigan Health Department. He says this policy requires homebuilders to hook up to public water if it’s available, or test new wells for TCE before they can get a permit.

“If we identify that this site can't support a safe on-site drinking water well, we don't issue the septic permit so they can't move forward with the building project and invest a lot of money only to find out that they have contaminated drinking water,” he says.

He says the size of the area covered by the policy grew by two square miles earlier this month.

The cost of clean water

The source of the contamination is an orphan site, meaning that the responsible companies, Mt. Clemens Industries and later Wickes Manufacturing, no longer exist and can’t be made to pay for it.

In 2002, the state funded the formation of the Mancelona Area Water and Sewer Authority, or MAWSA -- a local utility made up of the water systems of Mancelona, Mancelona Township, and two adjacent resort communities. In total, the DEQ has poured $27 million into monitoring, mapping, and extending municipal water to homes affected by the plume. Roughly 500 residences have had to abandon their wells and get hooked up to public water. At-risk wells, like Bethany Hawkins’, are tested frequently, and if TCE is found, the home is provided with bottled water until municipal water can be extended.

In addition to residential wells, two public well fields could be impacted by the plume. One is actually a source for the Mancelona Area Water and Sewer Authority, the public supply that affected homeowners are being hooked up to. In 2015, the state and Antrim County partnered to fund extra infrastructure that will supply clean water if this field becomes contaminated.

The other threatened well field serves another resort area to the northwest, and its future is less clear. Janice Adams says it could be absorbed into Mancelona’s system, or hook up to the next town over, Bellaire.

“At this point we’re quite a few years out for even that becoming impacted, so at that point we’d have to evaluate and see if it’s more cost-effective to hook them up to the City of Bellaire, the Village of Bellaire. So there’s options out there,” she says.

The DEQ has a couple more years’ worth of money to deal with the plume. But Adams says the voter-approved bonds that have supported this project since 2002 are nearly spent.

"The funding for this site comes from the Clean Michigan Initiative, and those funds are running out, but Lansing is working on other funding sources to be able to clean orphan sites up in the State of Michigan,” she says.

But people who live in the path of the plume, like Bethany Hawkins, are still concerned.

“Well, it's nice the DEQ is going to pay for getting me hooked up to public water, but what if somebody says 'oh, we're not going to fund that anymore'? You know, and with the state of the government at this point, it's just not very comforting to me to accept that assurance.”

State officials say it would cost too much to clean up the contamination. So, they say they’re just going to keep connecting homes to municipal water as the plume moves.