Hiding people in barns, or stowing people in secret rooms while keeping the watchful eyes of law enforcement and bounty hunters away from their clandestine activities. That's our image of Michiganders who helped thousands of escaping slaves through the Underground Railroad.

But there are many more dimensions to the Underground Railroad in Michigan.

Historian Michelle S. Johnson has made it her mission to help us more fully understand Michigan's role in the Underground Railroad.

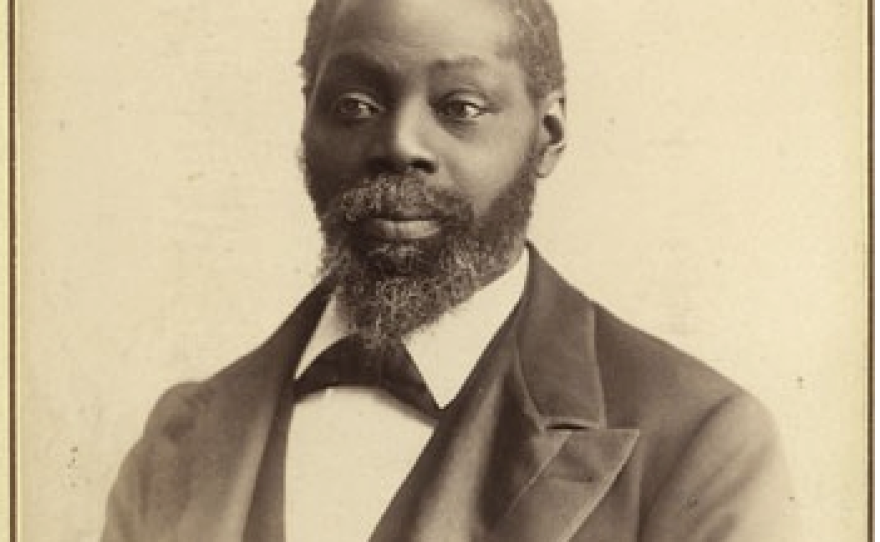

According to Johnson, people were escaping to Michigan far before the territory became an official state. Black people were not always fleeing slavery, but also segregation and racial inequality. Free people also moved north, leaving segregated southern communities behind.

As a result, the populations of black people living in Michigan were surprisingly spread out across the state, including communities not usually associated with the Underground Railroad or the fight against slavery.

Johnson says there were areas with large populations of black people growing in the 1840s and ‘50s, like Cass, Wayne and Washtenaw counties. Then there are little “blips,” Johnson says. Small areas or towns that ended up with a robust population of black people.

“Like up in Cheboygan where, in 1860 I think, you’ve got a large number of black folks,” Johnson said. “And you also find even in 1860 in Allegan and Van Buren Counties here in Michigan. These little pockets of folks, in Ionia for goodness sakes. So many places that we don’t typically think of black people in the landscape.”

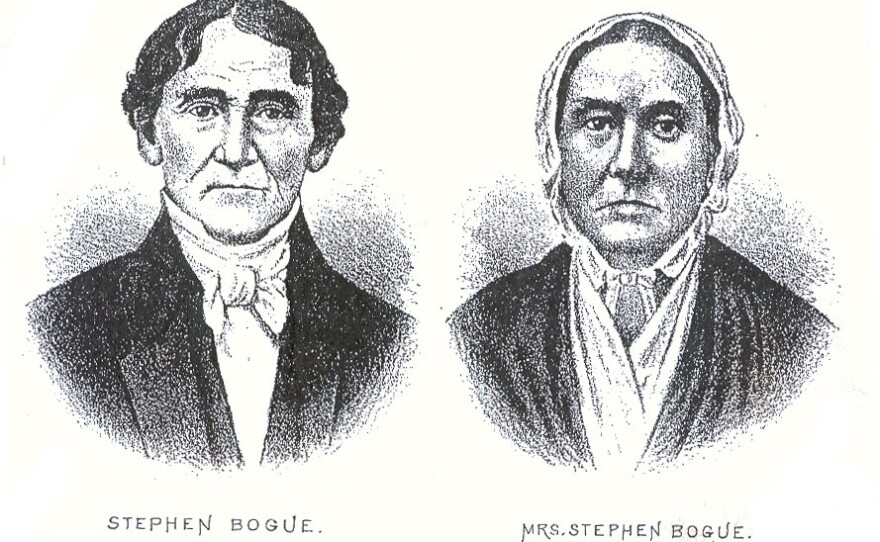

And it wasn’t always white people “secreting” people to their escape from slavery or racial injustice. Johnson says that did happen, but the social mechanisms of the Underground Railroad were more complex. Even in communities depicted as progressive enclaves, like the Quakers, there may have been strong anti-slavery sentiments, but that did not always translate to beliefs in equality, or action.

Typically Quakers are depicted as benevolent people that didn’t believe in slavery, which Johnson says is true, but it didn’t mean there was a consensus in the Quaker community about what should be done in regard to slavery.

“Should you just let God work it out? Or should you exercise a more radical political strategy?” Johnson said.

Johnson says there were ongoing debates and changing political climates as people considered what to do about slavery. And if someone was an abolitionist, it didn’t always mean they weren’t racist.

“People could operate out of this, what you might call a ‘missionary’ perspective, and not really be anti-racism,” Johnson said. “They could be anti-slavery and not really anti-racism.”

And there are things about the Underground Railroad that Johnson says people get wrong.

“One of the most common perceptions of the Underground Railroad is there were these routes,” Johnson said. “I’ve spent ten years trying to refute the notion of ‘routes’.”

Johnson says people fleeing slavery or discrimination traveled by navigating their own social networks of family, religion and social circles rather than following pre-determined routes on a map.

“It’s not like kind of laying out your [route],” Johnson said. “What you see then are these pulses of activity in these particular locations that when you have a decent population of black people in these various places in Michigan, it speaks to a notion of having safe space created for these folks.”

Listen to the entire conversation with Michelle S. Johnson above.

Learn about the Southwest Michigan Underground Railroad Tour, happening June 3, at the Society for History and Racial Equity's website.

This segment is produced in partnership with the Michigan History Center.

(Subscribe to the Stateside podcast on iTunes, Google Play, or with this RSS link)