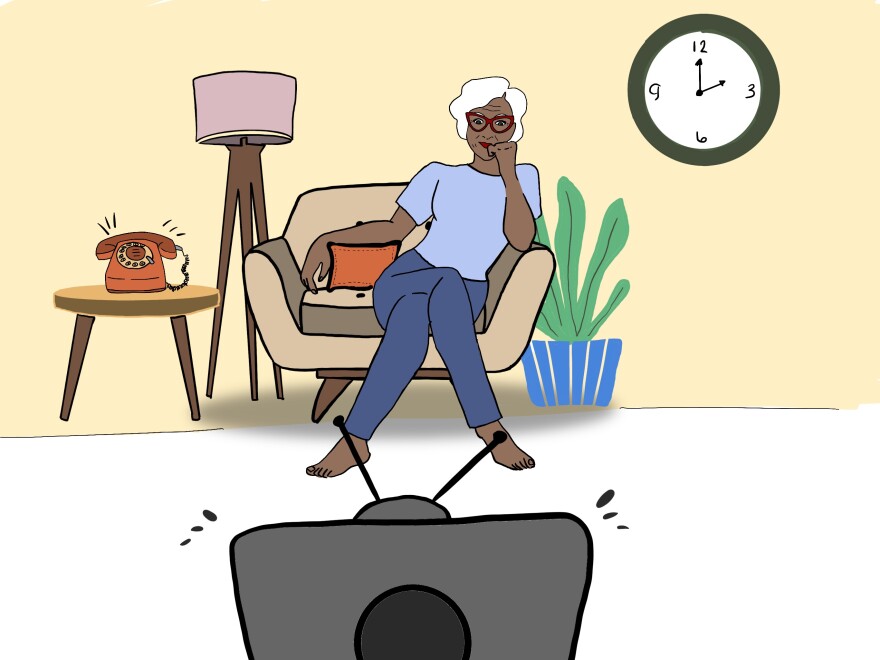

Every weekday at 2 p.m., 81-year-old Gladys Acklin settles into her couch to watch the soap opera “General Hospital.”

“We both like Sonny,” she says. “He’s the mobster.... And his hit man Jason. We like him too. We like all the crooks.”

When Ms. Acklin says we, she’s including Jean Reinbold, a social worker, but also a friend. Since the lockdown began back in March, Reinbold has been calling Ms. Acklin, who lives alone, quite a lot.

“Yeah, I would say, minimally, three to four times a week,” says Reinbold.

Reinbold works for the Detroit Area Agency on Aging, the largest of 16 such agencies in Michigan.

Created by a 1973 addition to the Older Americans Act, these federally funded organizations connect vulnerable seniors, veterans, and disabled folks with home- and community-based services.

Depending on the person, that could mean home-delivered meals, house cleaning, personal care, or a combination thereof — anything that will keep the participants at home in their communities, and out of expensive long-term care facilities.

Sylvia Brown, DAAA’s chief clinical officer, says part of the organization’s work is to look after the mental health of seniors living alone, who struggle with social isolation regardless of whether they’re living through a pandemic.

“When you're a senior, and you don’t have any family — or you have family, and they don’t reach out to you at all — you just lonesome. You just want to hear somebody, hear somebody’s voice,” she says.

Ms. Acklin could live in a nursing home if she wanted, but she would do so at the cost of ending a long history in her community. And right now, it would mean moving away from a place where she’s managed to stay relatively healthy and upbeat, and into one that would isolate her even further.

Michigan’s nursing facilities, whose residents make up about a third of the state’s COVID-19 deaths, only recently welcomed back visitors, and only under limited circumstances.

Ms. Acklin has been in her Detroit apartment since 1996, the year she retired from her job in the vault at the National Bank of Detroit.

But she misses the bustle in her neighborhood.

“I don’t go out a lot like I used to,” she says. “But since the lockdown, it started to get to me. I was getting down, you know, depressed and all that. I said, ‘Well, I’ll be glad when the weather changes, ‘cause at least I can open the door, and I would see people walking by.’ But I don’t see that anymore.”

Ms. Acklin gets help from her niece, who comes by three nights a week to make sure everything in the apartment is in clean, working order (of course, she wears a mask and keeps her distance).

Her nephew also swings by. He drops off ciabatta bread so Ms. Acklin can make her egg sandwiches, and tends the flowers by her front door.

DAAA coordinates meal deliveries, but sometimes Ms. Acklin prepares her own food in the slow cooker.

She thinks of her first-floor apartment, near Detroit Receiving Hospital, like a “small house.” On the living-room wall there’s a mirror, a picture of the Virgin Mary, and a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. Between the living room and kitchen she has an old stereo.

“The 60s music is what I used to love,” she says.

Whenever it came to Detroit she would attend the Motortown Revue, a concert series from the 60s that showcased Motown’s entire roster of artists.

She saw The Temptations and Stevie Wonder at the Fox; Gladys Knight, Marvin Gaye, and The Miracles; others she saw at Cobo Arena.

Part of that same facility — Cobo Hall, now the TCF Center — was converted into a giant field hospital this year to care for recovering COVID-19 patients.

Ms. Acklin’s friend Darlene got sick with the virus and was one of the few people who spent time at the TCF Center. Now that she’s on the mend, she and Ms. Acklin talk daily, though Darlene used to visit in person.

But not at 2 p.m.

“I don’t dare call Ms. Acklin at 2 o’clock,” says Reinbold, the social worker with DAAA. “She’s watching ‘General Hospital.’ ”

Reinbold says Miss Acklin is doing much better than some of her other clients. While the phone check-ins are no replacement for actual visits, she and Ms. Acklin alike have found solace in their conversations.

“I can talk to her like I would talk to my sister,” says Ms. Acklin.

Aside from her television, and keeping tabs on the slow cooker, Miss Acklin fills her day with other phone calls: Darlene, Thelma, old coworkers from NBD.

Her niece comes in the evening.

And despite the awkward distance, and not being able to see her friends, and the endless news, she keeps looking around the bend.

“I don’t care how bad things would get,” she says.

“To me, it was always going to be a better day, you know … I’ve always been that way.”