To successfully emerge from bankruptcy, Detroit has to find ways to cut spending and increase revenue. But that’s not going to be easy when so many Detroit residents are struggling just to get by.

No matter how well bankruptcy goes for Detroit, the city is going nowhere if most of its residents are broke and without jobs.

No jobs mean no income taxes for the city.

Income taxes amount to the largest category of taxes collected – close to four out of ten dollars collected – and Detroit needs those municipal income tax revenues to keep the streetlights on and the trash picked up.

That’s why companies coming to Detroit and hiring residents of Detroit is an exciting trend for Detroit boosters.

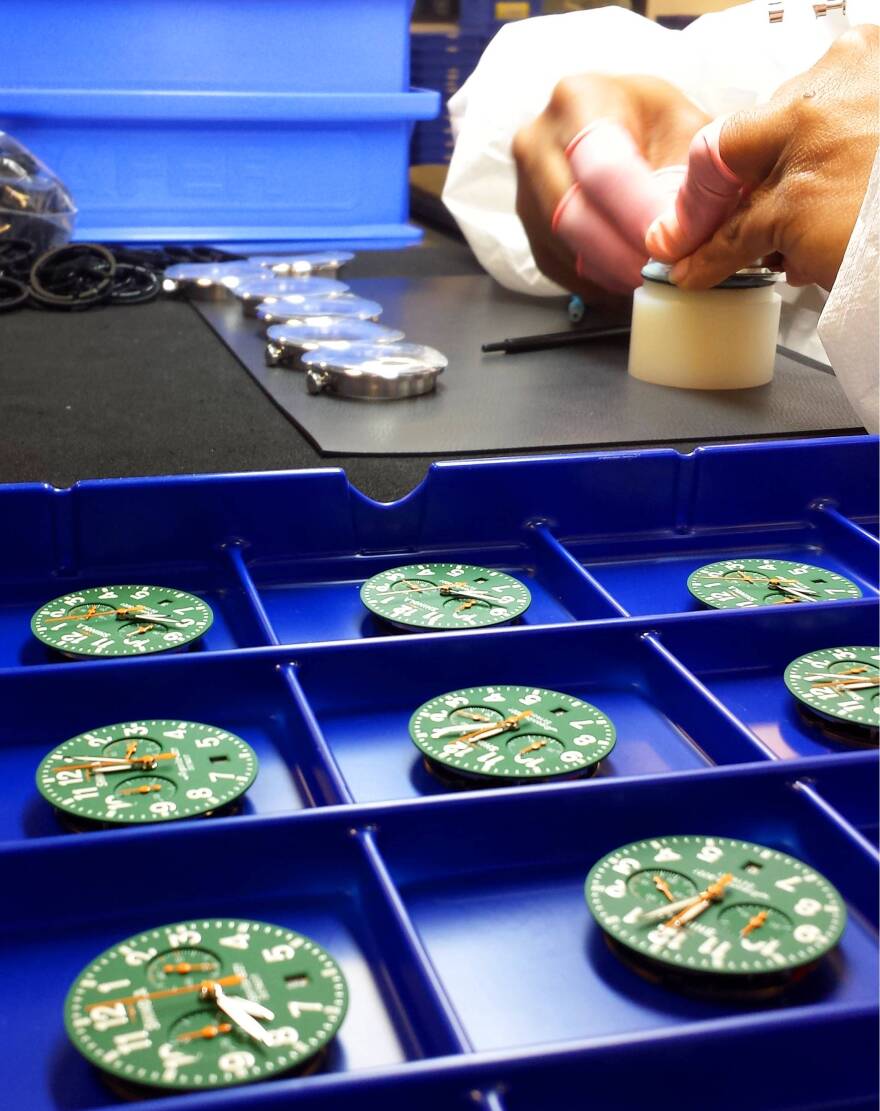

With a hair net on my head, a lab coat on, and little blue booties on my feet, I’ve been allowed on the assembly floor of a Detroit a company called Shinola.

It makes – among other things – watches. You don’t want any contaminants, like a hair from my head, messing up the fine timekeeping mechanisms that are being put together by about 225 technicians who work here.

Shinola is making its watches in Detroit as part of a statement. Watches from the gritty urban underdog sell pretty well in the upscale New York stores catering to hipsters or wannabe hipsters.

Shinola’s president, Jacques Panis, says there’s another reason to build watches in Detroit.

“Manufacturing is in the DNA of the people of this city, and we’re manufacturing watches here. Much like cars, car engines. You know, we have an assembly facility right here in Midtown Detroit,” Panis said.

He added if you like the city, want the city to succeed, you’ve got to make sure the people succeed.

“You know, it’s all from people right here in the city who are part of this inner-city community who are renting homes, buying homes,” Panis explained.

Three out of four people who work at Shinola live in Detroit.

They’re buying those houses and paying property taxes. They pay the city’s income tax. They contribute.

But Detroit is going to need a whole lot more resident taxpayers.

“My apprehension would be that after bankruptcy there still is too small a tax base to support the basic services that the city will need,” said Reynolds Farley.

He’s a professor at the University of Michigan. He says besides a lot of people abandoning Detroit in the last few decades, those who are left don’t have the kinds of jobs they used to have if they have a job at all.

"The wages of black men are about half in real terms now (compared to) what they were in 1970 and the poverty rate has gone up."

“One of the more discouraging things with regard to the black population is in 1970 the typical job was in vehicle manufacturing. Now the largest employer of African-Americans in the state of Michigan is the quick food restaurants,” Farley said.

That’s left those residents still living in Detroit with very little.

“And so, income of black families is down. The wages of black men are about half in real terms now (compared to) what they were in 1970 and the poverty rate has gone up,” Farley explained further.

There’s been a lot of news coverage of suburban corporate headquarters and thousands of jobs moving into Detroit. And it’s true, those corporate offices and jobs will help Detroit. Corporate income taxes help. And those people who live in the suburbs but work in the city will pay city income taxes.

But out-of-city residents pay half the income tax rate that residents do. And, according to a 2009 analysis, Detroit didn’t collect tens of millions of dollars that it was due from commuters from the suburbs and corporations.

The McKinsey Report also found Detroit loses out on some income tax revenues from residents who work outside the city. Employers outside Detroit are not required to withhold city taxes. It’ll take a new state law to fix that.

(See this Citizens Research Council of Michigan report.)

That’s why putting Detroit residents to work in Detroit is so important.

“It’s critical that we include everyone in these opportunities that are coming,” said Pamela Moore, who heads the non-profit Detroit Employment Solutions Corporation.

It used to be the city of Detroit’s employment agency, but because of the city’s financial struggles, it went off on its own in 2012. She says the city is only going to recover if prosperity is shared by Detroit workers getting jobs in the city.

We've got to stay focused on it because, again, we've got to increase property tax revenues; we’ve got to increase income tax revenues into the city. We’ve got to grow the city. We’ve got to address the crime. And when people are working, the crime is going to be reduced. And so, it’s all connected,” Moore said.

Jobs are scarce in the city. Of adult black men aged 25 to 59, you find only about 45% of them have jobs. So when a company comes to Detroit and makes a determined effort to hire people from Detroit, it matters.

A company called Detroit Manufacturing Systems which makes dashboards for Ford vehicles has hired hundreds of Detroit residents in the last couple of years. Whole Foods made a determined effort to hire Detroit residents.

And Shinola keeps hiring.

Willie Hollie hired on at Shinola before anybody had heard of the company.

“Before it used to be that I said I worked for Shinola and they’d say, ‘What? Shinola? What’s that?’ But now, they’re like, ‘Hey, you work for Shinola, right? You think you give me an in?’ Because, you know, there are still people out here looking for jobs,” said Hollie.

And those people getting jobs, investing in their homes and neighborhoods, spending money at local stores, and, yes, paying their taxes is the only way Detroit will be a functioning city after bankruptcy.

Michigan Radio is teaming up with a handful of other media outlets to look at Detroit's bankruptcy and its aftermath. The Detroit Journalism Cooperative will spend the next year exploring Detroit's future and what it means for the state.

Support for the Detroit Journalism Cooperative on Michigan Radio comes from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Renaissance Journalism's Michigan Reporting Initiative, and the Ford Foundation.