A year ago, the City of Grand Rapids released a study showing that black drivers are twice as likely to get pulled over as white drivers.

Since 2015, the most recent year considered by the study, the entire Grand Rapids Police Department underwent racial bias training. So we wondered, has anything improved for black drivers in Grand Rapids?

The anecdotes don’t look good. In March of 2017, GRPD faced significant backlash after officers detained five unarmed black teenagers based on a phone call. In December of 2017, an 11-year-old black girl was held at gunpoint while police searched for her (white) aunt.

Black residents Michigan Radio interviewed in the last month were not positive about the police, and Chief David Rahinsky of the Grand Rapids Police Department acknowledged that “there’s no magic potion for these types of issues."

But, what does the city’s latest traffic data tell us about whether Grand Rapids’ black drivers were being treated more equitably in 2017? We hoped to compare 2017 to past years, to see if the bias training and study results prompted a change for the better.

It’s complicated

Traffic stop data is difficult to analyze without oversimplifying or ignoring important factors that can -- and should -- influence how it’s interpreted. The more we dug, the more we understood why the city hired an outside consulting firm to conduct the study published in 2017.

We ran our initial findings past Michael Smith, chair of the Department of Criminal Justice at the University of Texas at San Antonio. He’s been studying this stuff for decades. Smith says it’s really easy to misinterpret traffic stop data -- and he’s seen newsrooms get it wrong before.

“Be careful not to oversimplify what are complex social processes in an effort to sell newspapers or clicks on a website,” he warned.

For every seeming pattern, there was an underlying set of factors that limited what we could conclude. We couldn’t find any data suggesting the city’s policing practices had improved. But, our evidence to suggest they haven’t has limitations.

So, we want to share what we DID find -- and take the opportunity to highlight the ways it’s easy to get traffic stop data wrong.

Are cops still pulling black drivers over more often? Yes. But…

For the last five years, black drivers have made up a steady (even slightly growing) portion of traffic stops in Grand Rapids. In 2017, they accounted for 42% of stops.

Since the black population of Grand Rapids has hovered around only 20% for almost a decade, those numbers seem to say that black motorists are overrepresented in traffic stops, and that things did not get better in 2017. But, those data can’t tell the whole story.

In an ideal world, we’d be comparing stop rates to driving populations, not the general population. The racial makeup of people driving in Grand Rapids or even a specific Grand Rapids neighborhood could really differ from those who live there. People working, going to school, and pursuing leisure activities in neighborhoods and cities they don’t live in could all throw things off.

Differing modes of transportation and the likelihood of having a driver's license could vary for different racial groups in the city. Studies around the country have found that being black makes you less likely to have a driver’s license and more likely to use public transit.

Michael Smith, the criminologist from the University of Texas, told us that social scientists worth their salt stopped using census data as a comparison for traffic stops more than a decade ago.

“At the municipal level, census data does not provide a valid estimate for the actual driving population of a city,” he says. “One must compare the population of drivers stopped (i.e. 40%) to [a] valid and reliable estimate of the population at risk for being stopped.”

The population at risk for being stopped is known as the benchmark, and a census benchmark doesn’t cut it. You can’t assume the racial makeup of Grand Rapids residents is the same as its drivers.

The second problem is that if you’re looking at stops on a citywide basis, you’re missing local policing patterns. It could be that police spend more time in black neighborhoods. And, if that’s the case, maybe that’s a problem in and of itself. But it doesn’t necessarily show that police are picking more black motorists out of traffic -- just that they’re spending more time where more of the drivers are black. Bias is best investigated hyper-locally.

It’s labor-intensive to take these factors into account. That’s why the city hired Lamberth Consulting.

Lamberth Consulting sent observers to 20 intersections around the city, where they spent time counting drivers of different races. For each of those 20 intersections, based on observer counts, they estimated the racial makeup of the driving population.

Then they compared that to the racial makeup of traffic stops at each intersection.

For example, at the intersection of Bridge and Stocking, black folks made up 15% of the drivers, according to the observer data. But in 2015, 31% of the motorists stopped there were black. That is evidence of possible bias.

Stop records that we received from the GRPD didn’t include necessary location info. So, we couldn’t compare the 2017 data to the Lamberth intersection benchmarks -- and we can’t definitively say whether things have gotten better or not.

Have search rates of black motorists changed?

What about what happens after a motorist is pulled over?

First, when trying to identify bias in searches, you have to remember that cops don’t always have a choice about searching somebody. If a motorist is arrested, their car will be searched no matter what. So, we narrowed our data to look only at searches initiated at the officer’s discretion.

Discretionary searches can include “consent” searches where an officer asks to search and a motorist agrees, or “probable cause” searches where the officer sees, hears, or smells something they think is evidence enough to force a search.

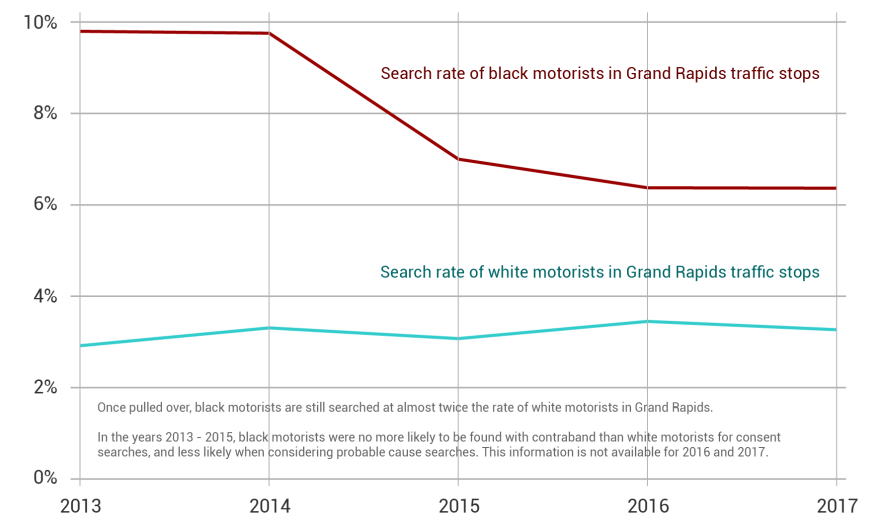

About 3% of white motorists who are stopped are then subjected to a discretionary search -- and that number has held steady since 2013. Discretionary search rates for black drivers dropped from 10% in 2013 to 6% in 2016 -- but they remained at 6% in 2017. Black motorists are still being searched at roughly twice the rate of white motorists.

There is another layer to this. Michael Smith brought up something called a “hit rate.” That’s the rate at which police actually find contraband among different racial groups. Police forces have previously argued that higher searches of minorities are due to higher hit rates among them.

The idea that it’s OK to search a racial group more often if they turn up with contraband more often is controversial. And Smith says that, broadly, searches of black motorists often turn up less contraband.

“Most (although not all) studies that have examined this question have found higher search rates and lower hit rates for blacks when compared to whites,” he says. “And that suggests that police may be applying a lower standard of probable cause (and therefore they are mistaken more often) for blacks than for whites, which raises an inference of possible bias, whether intentional or unconscious.”

Lamberth Consulting found that in 2013 - 2015, consent searches of black motorists in Grand Rapids were about equally likely to turn up contraband as those of white motorists. Probable cause searches of black drivers were actually less likely to turn up contraband compared to those of white drivers.

The data we analyzed didn’t say whether contraband was found at each stop, so we couldn’t determine a difference in hit rates for 2017. All we can say is that black motorists were still being searched twice as often as white motorists.

Are black motorists being pulled over for different reasons?

The stop data we obtained included the reason for each stop. Although these categories were sometimes vague, we noticed that the prevailing reasons for stops did seem to vary between white and black motorists.

For the last five years, the most common reason listed for pulling over white motorists was a “moving violation.” Starting in 2014, “equipment violation” became the most common stop reason for black motorists (equipment violations also jumped for white motorists starting in 2014, but remained secondary to moving violations). According to Smith, looking at differences in stop reasons across racial groups is problematic because we can’t say *why* these differences exist -- and some of possible reasons have nothing to do with police bias.

The fact that black motorists are stopped more frequently for equipment violations could be evidence that police are stricter with black motorists for things like broken tail lights. Or, it could have to do with factors like black drivers’ ability to afford new tail lights.

Another stop category where bias is hard to identify is radio calls, where black motorists are slightly overrepresented. For the 2013 - 2017 period taken as a whole, they comprise 40% of traffic stops, but 44% of stops based on a radio call. Radio calls are often initiated by citizens contacting the police, who are then obligated to respond.

“It likely means that police are responding to citizen complaints that disproportionately (44 vs. 40 percent, a relatively small difference) involve black drivers,” says Smith.

So, here, the disproportion could be explained by people calling in to report black drivers more often -- and not by police bias.

A more detailed analysis

It took a LOT of work for Lamberth Consulting to find evidence of bias in Grand Rapids -- and that evidence is solid. But, it’s difficult to recreate that work in the newsroom, at least with the information we were provided. The city will need to publicize more detailed data, or do updated analyses of their own in order to know for certain whether things have improved for black drivers.