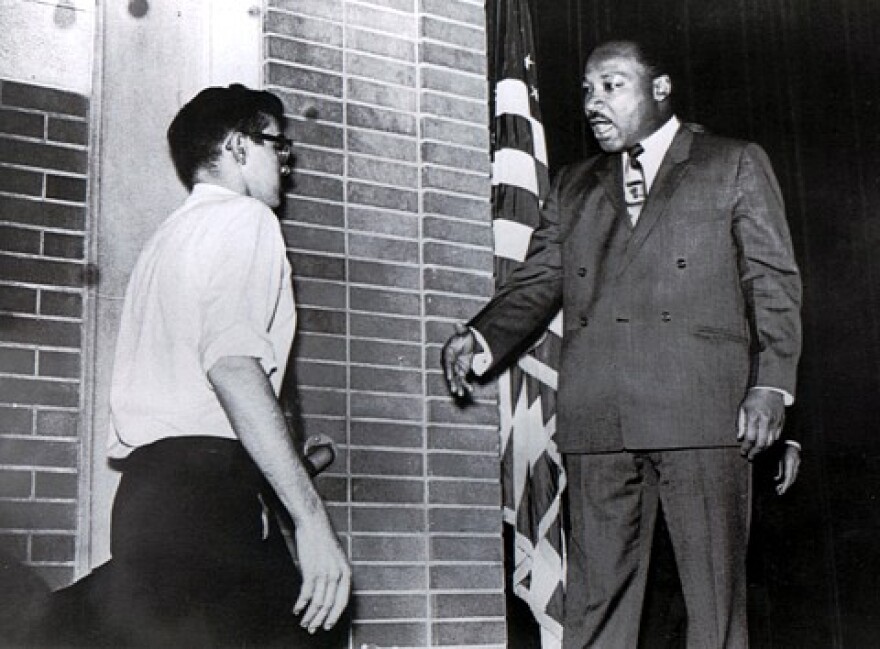

In March of 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Grosse Pointe, a nearly all-white Detroit suburb.

He gave a speech at Grosse Pointe South High School called “The Other America.” Three weeks later, he was shot and killed.

This past weekend, people gathered in that same gym to hear a recording of that speech. Nearly 50 years later, it still strikes a powerful chord.

(Support trusted journalism like this in Michigan. Give what you can here.)

I went to high school at Grosse Pointe South, and I knew King had spoken there. I’d even read the speech. But this past weekend, back in the same gym, I heard it for the first time.

It’s called “The Other America,” and it starts like this:

“I want to discuss the race problem tonight and I want to discuss it very honestly. I still believe that freedom is the bonus you receive for telling the truth. Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free. And I do not see how we will ever solve the turbulent problem of race confronting our nation until there is an honest confrontation with it and a willing search for the truth and a willingness to admit the truth when we discover it. And so I want to use as a title for my lecture tonight, "The Other America." And I use this title because there are literally two Americas. Every city in our country has this kind of dualism, this schizophrenia, split at so many parts, and so every city ends up being two cities rather than one.”

King goes on to say that in one of these Americas, “millions of people have the milk of prosperity and the honey of equality flowing before them.” But the other has a “daily ugliness about it that transforms the buoyancy of hope into the fatigue of despair.”

There are many remarkable things about this speech, which is worth reading in its entirety (you can find it here). The events that surrounded it are equally remarkable.

King came to Grosse Pointe at the invitation of a group called the Grosse Pointe Human Relations Council. Tensions were incredibly high, and security was tight. While driving to the school, the Grosse Pointe Farms police chief sat on King’s lap to protect him.

There were more than 2000 people in the gym in 1968, most of them eager to hear King speak. But also among them were more than 100 protesters. It was an organized effort on the part of a local right-wing group called Breakthrough. They heckled King, interrupting him a number of times, especially as he spoke about his opposition to the war in Vietnam.

But King carried on:

“Let me say finally, that in the midst of the hollering and in the midst of the discourtesy tonight, we got to come to see that however much we dislike it, the destinies of white and black America are tied together. Now the races don't understand this apparently. But our destinies are tied together. And somehow, we must all learn to live together as brothers in this country or we're all going to perish together as fools. Our destinies are tied together. Whether we like it or not culturally and otherwise, every white person is a little bit negro and every negro is a little bit white.”

Diana Langlois, who lives in Grosse Pointe Woods, was among the diverse crowd of a few dozen people who

came out to hear King’s speech again on Saturday.

“I just felt like I wanted to hear his words. I wanted to hear him say it,” Langlois said.

“And it was very powerful, being in the gym where he spoke. You could almost close your eyes and sense what was going on back then, the animosity in the audience, and the hecklers and stuff like that. It’s so much like what we see today.”

Langlois echoed what nearly everyone there remarked on: how contemporary the speech felt. When King talked about racial hostility, political polarization, even the inadequate schools too many kids have to attend--it all felt very familiar.

It’s the first time, as far as anyone knows, that people actually gathered at the school to hear King’s speech since it happened. The event was organized by the new Grosse Pointe-Harper Woods chapter of the NAACP.

“When it was brought to our attention that he spoke here and there was audio …what else could we do, you know? It was just fabulous to be able to do that,” said Elaine Flowers, head of the chapter’s education committee.

Flowers said there will be more events honoring this going forward, especially as the 50th birthday of the speech and King’s assassination approaches next year. “We have this chapter of the NAACP with the mission of developing a community with love, diversity, and unity. And Martin Luther King…that’s his legacy,” she said.

The Grosse Pointes, and Metro Detroit at large, have as much an unresolved legacy of historic racism as any place in this country. And with that feeling of how little has changed, it would have been easy enough to leave with a feeling of despair.

But that wasn’t how it was.

“We’re still where we were. But we’re not, because you guys inspired me today,” Sharon Bell got up to tell the crowd after King’s speech had finished.

Bell lives on the east side of Detroit, a place she proudly told everyone she chooses to live. But she says lately, she’s been trying to reach out across borders and comfort zones.

“I wanted to get to know you,” she said. “And today I’m here and I see you. You gave me hope today. What it meant to me today was, there’s still hope alive.”

Denaria Thorn also lives in Detroit, and she felt the same.

“I felt like I was there. And I felt the pain. I felt the hurt. And at the same time, I felt the love,” Thorn told me.

Thorn also said something that struck me when really hearing this speech for the first time, too. About how King sounded like a man who knew he was going to die soon.

“You could tell he was somewhere else, even when he was speaking,” Thorn said. Like he said, he had already been to the mountaintop.

“He was on assignment. And he was going to finish that course, whether it meant death at the end, and he knew that. He knew that. But it didn’t matter."

After the speech was over, in 1968, one of the organizers accompanied King back to his downtown hotel. Her name was Jude Huetteman, and she wrote beautifully about it for the Detroit Free Press a few years later.

She recalled that they spoke about “hate and how it fills a man until nothing more can get into him…and about the inevitable and how it happens no matter how one plots against it.”

Huetteman thought she would never see King again. But she did, just three weeks later, in a casket at his funeral.

This is how King ended “The Other America,” on March 14th, 1968 in Grosse Pointe:

“We are going to win our freedom because both the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of the Almighty God are embodied in our echoing demands. So however difficult it is during this period, however difficult it is to continue to live with the agony and the continued existence of racism, however difficult it is to live amidst the constant hurt, the constant insult and the constant disrespect, I can still sing we shall overcome. We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. “We shall overcome because Carlisle is right. "No lie can live forever." We shall overcome because William Cullen Bryant is right. "Truth crushed to earth will rise again." We shall overcome because James Russell Lowell is right. "Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne." Yet that scaffold sways the future. We shall overcome because the Bible is right. "You shall reap what you sow." With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to speed up the day when all of God's children all over this nation - black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old negro spiritual, "Free at Last, Free at Last, Thank God Almighty, We are Free At Last."