More than 7,000 people were swept up in mass arrests during the 1967 Detroit uprising.

Jails and police stations were overflowing, so many people were held in makeshift detention centers, often in squalid conditions.

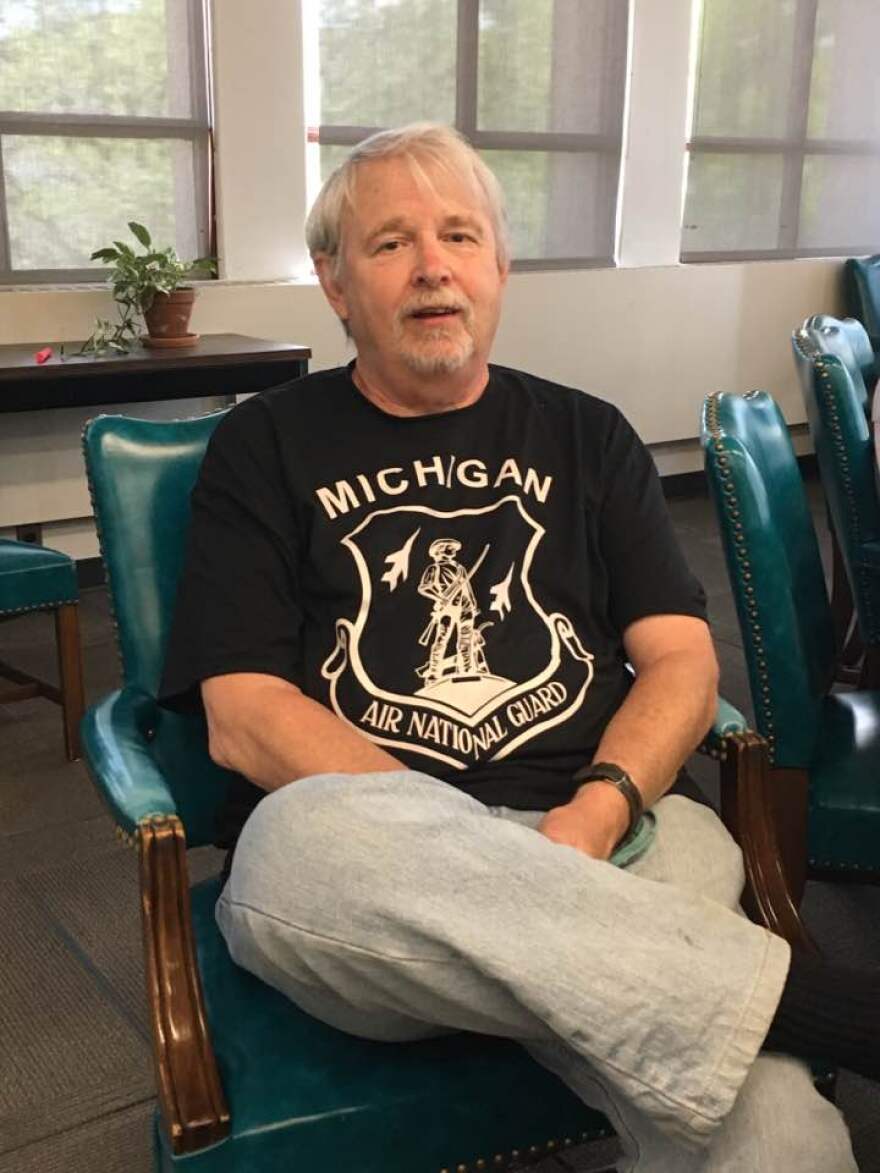

Jim Atkin was a member of the Michigan Air National Guard at that time. His unit was called up to try and contain the situation in Detroit, and his first assignment was guarding people taken into custody during the initial days of the chaos.

Atkin spoke with Michigan Radio's Sarah Cwiek about the experience for Stateside.

Atkin joined Air National Guard in 1965, with the 191st Supply Squadron.

“My group were basically college students,” he said. “There was a few people that were probably over 30, but basically it was a very young group.”

When the 1967 uprising got started in the early morning hours of Sunday, July 23, Atkin’s unit wasn’t called up right away.

He ended up spending a night at Detroit Metro Airport, which was transformed into an ad-hoc base camp. Then the guardsmen got on buses, and headed down I-94 toward Detroit.

“As we got into, probably around Livernois, they said, ‘pass this around and take 10 rounds [of ammunition],’” Atkin said. “That was the first time that some of these guys, and myself, said ‘this is for real.’

“So we loaded our weapons.” They said, ‘There are snipers down here, don’t look at the roofs, look at the second-floor windows.’ And that was the extent of our training for the riots: ‘Load your guns and watch the second floor.’”

They finally arrived at the First Precinct in the heart of downtown Detroit, which had been turned into a fortress. Atkin said it was a surreal scene.

“There’s huge sand bag bunkers built about 10 feet high up and they had spotters, snipers, barbed wire all over the place,” he said.

More than a dozen city buses were parked outside, crammed full of people who had been arrested. With jails and police stations overflowing, authorities were jamming people into whatever spaces they could find.

Atkin says it was a mixed group of men: most black, but some white; old and young. They ranged from suspected snipers, to people picked up for simple curfew violations. And by that point, some of the prisoners had been there for a day or more.

“It’s hot. These buses smell bad. It wasn’t nice,” Atkin said. “I didn’t want to be there, and I know they didn’t want to be there.”

Atkin’s orders were to keep people on the bus, so there was no question of escorting people to the bathroom. It smelled strongly of urine. The mood was tense and volatile.

Atkin says he alternated between feeling sorry for the prisoners, and doing what he had to do to maintain order.

At one point, “One gentleman was in the middle of trying to kill his seatmate by smashing his head through the window and trying to cut his throat on the broken glass,” Atkin said. “I went to the front door of the bus and just stuck my bayonet in the front door so no one could come down.”

It's hot. Those buses smell bad. It wasn't nice.

Atkin was relieved when the detainees were finally taken to Belle Isle, which had been turned into a makeshift prison camp. By then, some of the prisoners had been on that bus for days.

But conditions on Belle Isle were still far from ideal. Many detainees remained there for days, as the overwhelmed court system improvised a version of justice under martial law.

Most of the thousands of people arrested eventually pleaded guilty to misdemeanors. Few were sentenced to any jail time.

But the whole experience was life-changing for everyone involved, including Atkin. He says before this, he had been a relatively naïve kid. But afterward, he started thinking and learning more about the conditions and inequities behind the violence.

With 50 years of hindsight, Atkin now sees the events of 1967 differently. “After that night, I did not know what happened to these individuals [arrestees], or how that affected their lives,” Atkin said. “It affected mine.”

Listen above to hear the full interview with Jim Atkin.