For victims of violence, the recovery process usually goes far beyond healing from physical wounds.

But many never get help dealing with trauma and its aftermath. And sometimes, victims are treated like criminals — especially if they’re young and black.

Some people in Detroit are trying to change that. This is the story of one young man who got shot, and two people — and two organizations — helping him remake his life.

Antwan: “This wasn’t supposed to happen, but it happened.”

Antwan Green wasn’t doing anything wrong when he got shot. In fact, he was trying to do the right thing.

Green is a Detroit rapper, better known as Guapo. He’s developed a following and performed all over the country. He’s 25, self-confident, and has dreams of moving out to LA, where he lived for a couple years as a teenager.

If you look closely, though, you’ll notice that Green holds his right arm a little awkwardly. That’s because of what happened after a performance at a Detroit night club last year, when a drunk, angry woman followed him back to a house.

Green didn’t want to fight. He called a friend to pick him up. But the woman got angrier. As they tried to leave, she rammed their car from behind.

“She ran us into an abandoned house. The car flipped over twice and caught on fire,” Green said. “So I’m only talking to you all with the grace of God.”

Green’s friend was carrying a gun that night. It went off during the accident, and ripped through Green’s right hand. After the crash, he stumbled to a nearby gas station.

“I was in so much pain, I just laid down and asked for some water,” Green said. “Next thing I know, I was waking up signing the papers for a blood transfusion at Sinai.”

The emergency room at Detroit’s Sinai-Grace Hospital sees more shootings, stabbings, and other traumatic violence injuries than any other ER in the state. It’s also home to a program called Detroit Life Is Valuable Every Day — DLIVE, for short. Its mission: stopping violence by treating it like a public health problem.

When Green was there, someone came to his bedside. He talked to Green about the cycles of violence, the odds of becoming a victim again.

At first, Green was offended. This hadn’t been his fault. “I was explaining to him, like, I have my music thing going on, this wasn’t supposed to happen, but it happened,” he said.

But, with his bullet wound still fresh and in intense pain, Green agreed to come to a DLIVE meeting at the hospital. There, he found other victims of violent trauma. They got what he was going through. They wanted to help him heal — and to never have to go through this again.

That turned Green around, fast. Today, he describes himself as an “avid DLIVE member.”

“The way that they embrace you like a real family, it’s like having uncles,” Green said. “And I can relate to them a lot.

“It gives me the umph, like I can stick my chest out like. I got somebody that’s got my back, no matter what.”

Calvin: “It’s a ministry.”

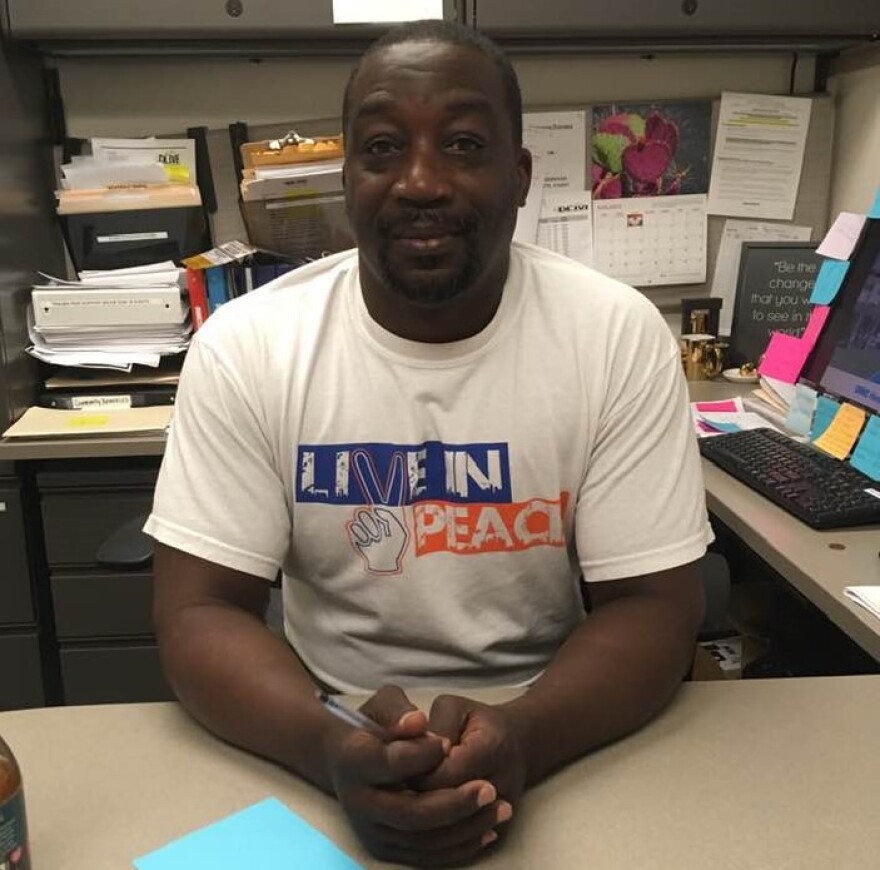

At a small office tucked away inside Sinai-Grace Hospital, Calvin Evans is trying to catch his breath after a busy morning, spent counseling the mother of a DLIVE member worried about her son.

“It’s a ministry. And you can’t retire from ministering,” Evans said, laughing.

Evans is a DLIVE co-founder and violence intervention specialist. That’s the person who shows up at patients’ bedsides at Sinai-Grace, at what Evans calls “the teachable moment.”

Evans knows about violence. Years ago, he was a victim himself.

“And no one came to my bedside to offer the sort of services that I offer,” Evans said. “In fact, when I was stabbed in the leg and I came in, the nurse told me that in six months, I’ll be back with a gunshot wound.”

"Our system actually pushes those individuals away, and they end up dead, or in our failing jail system." --Calvin Evans, DLIVE

“The way she conveyed it to me was punitive. It was criminal. It was the language in which, as a society, we utilize to describe someone who has been a victim of violence. They are the problem.”

In fact, Evans did come back six months later with a gunshot wound to the mouth. And that’s the thing about violence: Being a victim once makes you more likely to be a victim again.

“Violent injury is a reoccurring disease,” wrote a group of researchers who studied victims of violence in a Flint emergency department over a two-year period. The 2015 study found that youth who had been assaulted “had almost twice the risk for a violent injury requiring ED care within two years,” compared to peers who presented with other medical issues. This phenomenon is particularly common among young, African-American men.

DLIVE is the brainchild of Dr. Tololupe Sonuyi, a Sinai-Grace physician. Treating victims of violence every day, he started to think: What would it really look like if we treated violence as a public health problem? How do we stop the disease from spreading? And for those already suffering from it, how do you prevent them from getting sick again?

Sonuyi recruited Evans to help make his vision a reality. That was in 2016. Three years later, it has more than 140 members, and is rapidly expanding to other hospitals. That’s because it seems to work: So far, only one DLIVE member has suffered violent re-injury.

“We’re teaching the world something different with regards to the issue of violence, and how we are to treat it,” Evans said. “This is the dosage that is needed in order to cure this issue. This is the medication.”

But what is that medication, exactly? According to Evans, it’s “understanding trauma and how it works. We utilize that to teach trauma. We become trauma educators.”

But Evans’ work goes far beyond the bedside. He’s out in the community, working with DLIVE members and their whole social networks — part social worker, part epidemiologist — doing anything he can to stop violence. After being a repeat victim of violence, and spending 24 years in prison, he says he’s a living example that there’s a way out.

“I died, and I’m reborn. I’m not who it is that I was. And I can give birth to other people,” Evans said.

“Our responsibility is, how we do service those individuals? Our system isn’t aligned with that thought, that idea. Our system actually pushes those individuals away, and they end up dead, or in our failing jail system.”

If violence is a disease caused by certain social conditions, treating it means changing those conditions. And that means meeting people’s needs — for support and affirmation, but also for more concrete things like jobs and housing.

Erin: “They need somebody who can be an ally.”

Sometimes, DLIVE members have legal needs. Antwan Green knows about that firsthand.

“When I first got shot I was actually arrested on my tickets,” he said. “I was like locked, chained to my bed for the first two days.”

Green didn’t have a criminal record. But he did have a lot of traffic tickets. That’s really common in Detroit. Green had never gotten a driver’s license. But that meant he had warrants out for his arrest.

“For so many young people, a barrier to them getting back on track after they have been shot, is warrants,” said Erin Keith, the youth legal services and empowerment attorney at the Detroit Justice Center.

"He was my first client. I really wanted to see him win."--Erin Keith, Detroit Justice Center

Green was Keith’s first client ever. DLIVE connected her with Green; she went to the hospital and had a conversation with him and his girlfriend. They made a plan.

“Then he kind of ghosted me, so I had to kind of find him,” Keith said. “I was texting him like, 'Antwan, we had a whole conversation, we’re going to do this.' You can get a job at a plant and work a nine to five while building your music career. But if you have warrants, a lot of times you can’t get those kinds of jobs.

“He thinks it’s not a big deal until he starts applying for jobs, and DLIVE can’t do the things that they want to do to help him get fully situated because of these warrants.”

But Keith was persistent, and finally Green came around. Eventually, they cleared his record, and Green got his license for the first time at age 24.

“He was my first client. I wanted to see him win. I really wanted to help him,” Keith said. Today, she and Green have a kind of big sister-little brother relationship (it helps that Keith is only two years older than Green).

Since then, Keith has worked with a lot of DLIVE clients. They have different needs, legal and otherwise. Keith says she and her Detroit Justice Center colleagues strategize about how to best meet them, and be “good advocates for the whole client, and not just one little carve-out of their legal needs.”

There are all kinds of needs “that people may not associate with the actual gun violence itself,” Keith said, “but when a person is trying to recover and get housing, especially safe housing, get back on their feet, they need somebody who can be an ally to help with those things, as DLIVE works through the trauma.”

Housing has been identified as a particular barrier, particularly for people who experienced violence at or near their homes. The Detroit Justice Center is developing plans for a housing center that would serve DLIVE clients, though Keith says it’s still in the beginning stages.

But in the end, Keith says it all comes back to treating trauma.

“That’s why DLIVE exists, and that’s why I think they’ve been so successful, is they try to attack it not from a respectability politics, if you just pull up your pants or do this or do that … they’re like screw that, this is trauma,” Keith said. “Until we deal with this trauma, you can’t move on.”

As for Antwan Green, he’s doing OK now. He’s working a nine-to-five job at an auto supplier and still performing. He and his girlfriend are expecting their first child next month.

Green says his support network really helps. So does his music.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRVLuVWFm70

“I made a lot of songs about my pain. I feel like it impacted my music because it made me tell the truth,” Green said. “I had to be like raw with myself.”

Sharing his story helps too. Green says no one should have to recover from violence alone.

“This is a situation that most people can’t get through by themselves,” he said. “If you feel like somebody’s listening, it gives you like a sense of humility, you know? So I feel like, if you’ve been in this situation, find the help you can.”