Lorenzo Garrett felt abandoned when he was in prison.

“No one really cares about you,” he said.

In prison, you get used to a limited routine, he said, and that routine was thoroughly shattered during the coronavirus pandemic.

Garrett said he contracted the virus last April and was quarantined for more than a month. Garrett said he was in pain, but unsure if it was COVID or the hip consultations that were put off temporarily. He was moved to a unit that he described as unsanitary. In the beginning, some prisoners didn’t want to disclose their symptoms for fear of losing the little freedoms they had, he said, and he saw other men get sicker and sicker.

In the first months of the pandemic, Garrett described inconsistent mask use among guards, and those who were wearing masks got them “well before” the prisoners were offered them. He said he saw some people get disciplinary tickets for making their own face coverings since it was against the rules.

Visitations were closed. Phone calls were limited. Food was cold. No yard and recreation. He and the others were glued to the TV for more information for an explanation of what was happening outside.

“‘Is it going to come in here and kill us?’” they wondered in the first months. “Because we (were) looking at the deaths that (were) happening out there on the news.”

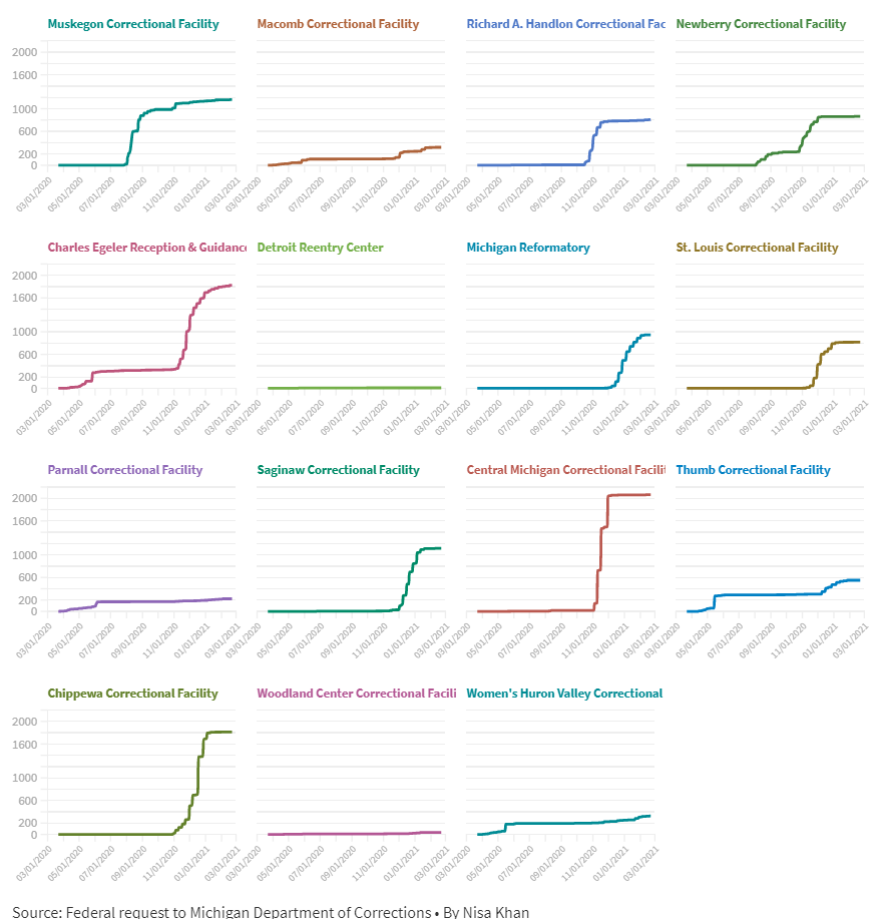

Garrett was part of the 26,025 total positive tests among Michigan’s incarcerated population in the past year. There have been 139 deaths and 41,130 tests as of March 29, 2021. According to a federal request, there have been 3,236 total hospitalizations as of March 5th.

Garrett was granted clemency by Governor Whitmer in December of 2020, but during his last year in prison, Garrett saw first-hand how the coronavirus ripped through Michigan correctional facilities.

And to advocates like Safe and Just Michigan's Josh Hoe, if you were going to design the worst place for a pandemic to occur, prison would probably be that place. From the structure of the prisons to the number of people, outbreaks are the nature of these places, Hoe explained.

A father of an incarcerated man, criminal justice advocate Pete Letkemann, told Michigan Radio he expected his son to get coronavirus.

These traits make prisons, and jails, something of a multiplier of disease, Harvard University researcher Eric Reinhart explained.

It was because of these experiences, Garrett said, that made most of the people he knew inside want the vaccine.

“We all wanted to take the vaccine,” he said. “We (were) taking every preventive measure that we could to try and not contract the virus. Because we have seen so many guys in there die. We have seen so many of them die and it was like, ‘He’s not coming back.’”

Despite a very high risk of infection, incarcerated people were not mentioned in early versions of Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s vaccination plans. Correctional officers were given priority as frontline essential workers.

This changed on March 12, according to Lynn Sutfin, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson. “Detained people” were added to group 1-B of Whitmer’s vaccination plan.

“This was done due to shared increased risk of disease and the difficulty in controlling outbreaks in correctional facilities,” she wrote in an email. “Also, based on the anticipated amount of vaccines becoming available to the state and President Biden’s directive that all adults should be eligible by May 1, Michigan has updated its prioritization guidance to move forward with allowing Michiganders who were not previously eligible to begin receiving vaccine(s).”

This was something many have pushed for since the beginning of the vaccine rollout. Tony Gant, a regional coordinator with the criminal justice organization Nation Outside, said he was involved with the vaccine rollout at a Genesee County Jail that offered one to everybody within the county jail.

"Because especially with jails — you have a lot of people in and out of jails. So it would kind of shoot ourselves in the foot if we don't vaccine people incarcerated,” he said.

Chris Gautz is the public information officer for the Michigan Department of Corrections. He says the MDOC’s new plan is to have bulks of 4,500 vaccines and start vaccinating everyone at select prisons at a time, as opposed to giving vaccines to every prison. The last batch of 4,500 doses went to prisons like Lakeland Correctional Facility, where many older people reside, and the Women's Huron Valley Correctional Facility.

Chris Gautz said they vaccinated about 15,000 prisoners and 1,300 out of almost 9,000 correctional officers.

Gautz is unable to provide numbers for correctional officers who got a vaccine at a pharmacy or institutions outside of MDOC. But there have been reports of many correctional officers turning down the opportunity. For Michigan correctional staff, there have been four deaths and 3,857 positive cases. Gautz said MDOC was promoting the vaccines and making them very accessible for officers.

In Mid-Michigan Medical Director Jennifer Morse’s experience, law enforcement and some first responders do not readily take to vaccines, like flu shots. And in Northern Michigan's more conservative counties, Morse’s office has been trying to work against anti-vaccine meetings and mailers. It depends how one approaches the situation and educates people, she said.

“And I don't want to generalize, but yes, it's been disappointing," Morse said. "Even in the face of an outbreak, we've seen pretty poor acceptance of the COVID vaccine. We do have jails that are asking us to set up COVID clinics for their prisoners, and so we'll see how well they take it up. But there’s also been a group that has been quite hesitant to vaccinate, whether that comes from just some of them being younger and not feeling that they need it, or just distrust of governmental organizations.”

And it’s important to get as many people vaccinated as possible — for people both inside and outside of correctional facilities.

An acceleration of cases

Safe and Just Michigan policy analyst Joshua Hoe explained that some of Michigan’s larger prisons are like pole barns, an open area that holds lot of people. There is also little space, meaning social distancing is impossible.

“You have central air and cooling and all kinds of other things, and so the germs kind of just circulate around a very densely packed group of people,” he said.

Hoe also said that prisons are likely reflective of the surrounding community’s cases, but surges in the community will accelerate “a lot faster” in enclosed spaces.

“And the reason they're at risk is because the community brought it to them. You know, nobody was sentenced to die from COVID-19,” he said. “We have a real responsibility to take care of them, and to consider them as an important part of our public health and safety response because they had absolutely nothing to do with the virus getting to them.”

Reinhart, the Harvard researcher, worked on a study that showed how a Chicago county jail affected many zip codes’ case numbers. The jail’s officials denied the findings, but Reinhart and his colleague stand by their work.

Jails are different from prisons — jails are a place for people awaiting trial or held for minor crimes. So there is much more movement in and out of the facility. Reinhart said jails and these cases tend to affect communities that are highly policed.

“Diseases come in from the community, people come into these facilities with tuberculosis, HIV, hepatitis C, influenza,” he said. “Cases come in, and cases go out back into the community, but in the process, in the space between, they multiply. So these facilities operate as what we call epidemiological pumps.”

But prisons see movement too, he said, with roughly 400,000 staff in and out of facilities every day in the country.

Reinhart also pointed out there is an economic angle.

“These individuals who are sickened by mass incarceration, a lot of their lives, their life expectancy is significantly shortened. Nobody likes to be sick,” he said. “And it also burdens an already overburdened healthcare infrastructure by not preventing disease when we could have prevented it.”

Correctional health care historically has been analyzed separately from community health, when they are interconnected, he said.

Prisons and jails are porous

Dr. Morse is not only the medical director for the Mid-Michigan District Health Department. She also covers the Central Michigan District Health Department and District Health Department #10.

That means the places she works with, like Gratiot or Montcalm County, also have large prisons. But MDOC works separately from her office.

“Certainly, when (a prison has) an outbreak, it does affect our community, because a great deal of our community is employed by the prison systems. And so whenever there is an outbreak in the prison, it inevitably will affect some of the staff,” she said. “And then I can't really think of times when that didn't lead to additional cases within the community.”

“It can go both ways; they can go from staff to prisoners, or prisoners to staff and then staff to community members,” she said. Morse also explained there were some cases of monitoring incarcerated people who have been released or transferred.

Criminal justice non-profit Prison Policy Initiative released a report in December detailing the possible association between public health and mass incarceration, using data between May and August 2020 and controlling it for various external factors. The report said it did not want to place blame on incarcerated people or correctional staff, but “rather, the complete mismanagement of the pandemic explains the large number of cases linked to mass incarceration.”

It stated that nationwide, cases grew more quickly in non-metro counties with more people incarcerated and in multi-county economic areas with more people incarcerated. Nationally, the Prison Policy Initiative hypothesized that half a million additional cases in and out of facilities were linked to mass incarceration.

The PPI report estimated that Michigan has had over 4,700 additional cases of COVID-19 linked to mass incarceration last summer. The top three Michigan counties, all non-metro with a smaller population, with additional cases per 100,000 people are:

- Ionia County at an estimated 5,145 additional cases with 141.91 per 100,000 people

- Gratiot Count at 3,742 additional cases with 121.68 per 100,000 people

- Branch County at 2,733 additional cases or 104.77 per 100,000 people

Wanda Bertram is the communications strategist at the Prison Policy Initiative. She said the research was a way to show a cumulation of the United States’s reliance on incarceration and how “warehouse conditions” frequently see outbreaks of disease.

“We wanted to look and see and show how outbreaks in these facilities lead to public health deteriorating outside the facilities as well,” Bertram said. “Because even if you don't care about people in prison, you should care about, at the very least, people in your community and people in your community are also being impacted by this.”

Gant from Nation Outside, said the report’s numbers are troubling.

“And when you add in the fact that it looks like the majority of correctional officers are refusing the vaccine right now, community spread is probably going to be something that the community should be concerned about moving forward as well,” he said.

Michigan Department of Corrections spokesperson Chris Gautz called the report flawed and did not take it seriously. Gautz said in regards to mitigating spread in and out of correctional facilities, the staff is told to take precautions seriously when they are on the clock. He added MDOC does not have say over staff members’ personal choices but encourages them to avoid large gatherings.

“When you look at Michigan, every county in the Upper Peninsula that doesn't have a prison has higher cases of COVID per million than the only UP county with two prisons,” Gautz said.

University of Michigan assistant professor Jon Zelner studies epidemiology. He said of the Prison Policy Initiative report that he is conservative when it comes to drawing connections between prison outbreaks and community spread.

“It’s not impossible, but it's hard for me to believe that that's a very important driver of risk at the community level in the sense that jails and prisons are just feeding tons of cases into the community that wouldn't have been there otherwise. But instead they're just kind of another reflection of a collection of social and economic factors that are driving these disparities,” Zelner said.

He said other structural factors may play a bigger role.

“I think in all likelihood, transmission in these facilities impacts risk in the community. I think that's true. But I think the flip side of it is that these places are kind of mirrors of the communities that people are coming from,” he said.

Zelner said he looked at prisons and jails as less of a case example but “another fact of the great machine of American social and health inequality.”

Releases

Along with more vigorous vaccination, another issue advocates called for at the beginning of the pandemic was early releases to depopulate jails and prisons since they said social distancing was just not possible in correctional facilities. Some family members, like Idalis Pagan from Grand Rapids, tried to set up petitions to get their family members released early.

MDOC has told Michigan Radio before that the state does not allow for early releases.

Pete Letkemann, the vice president of Citizens for Prison Reform in Michigan, said there is a difference between early releases and releasing people who may, for example, not have been able to take the right class for their parole, the latter being a requirement set by MDOC.

Releases in jails in other states have given good results. Reinhart explained that a study shows that even depopulating by a quarter, which is very doable he added, could bring down the transmission rate by 50%.

“And as far as decarceration, moving forward, I don't think this is going to be the last pandemic we see. And so I think it's smart to start looking at ways to ease the population strains in our prisons and jails across the board,” Gant said, adding that jails had cut their populations down drastically. “I just hope they learn from those lessons that COVID taught us around a pretty minor arrest and holding those people with minor arrests in the county jail.”

Advocates like Gant and Hoe hope to see changes in Michigan’s truth in sentencing law, which requires people to serve their full minimum sentence regardless of good behavior.

“This is a really punitive law,” Gant said of people held for decades. “And I think we could find smarter ways to deal with a prison population than just holding them indefinitely, or holding them and not allowing them to receive any incentives for what is ultimately great behavior in the prison population.”

“One thing that I think is difficult for people to get their heads around, but it's nonetheless probably true, is that a lot of the people who are most at risk in prison are elderly people who were sentenced for something that had come with a long term,” Hoe said, saying people incarcerated for over five years had little risk of repeating the offense.

“When someone's eighty years old, and done like 30 years in prison, they're not a real risk to the community anymore,” he added. “From a taxpayer’s perspective...by getting those people through their programming, and to their parole date where they can be paroled, you've saved around $35,000 per person.”

Zelner, the U-M epidemiologist, said he hopes for wide-spread systematic changes that could help incarcerated people — and the issues that feed mass incarceration, like socioeconomic inequality.

“We just have to constantly put band-aids on gaping wounds, and so we're less effective,” he said.

"We just have to constantly put band-aids on gaping wounds, and so we're less effective."

Garrett was one of four people who were notably commuted by Governor Gretchen Whitmer last December. Each had extremely long sentences related to non-violent crimes — Garrett himself had a 29 to 170-year sentence for delivering drugs.

The day he heard his case was going to be heard, he almost didn’t believe it. “You never want to get your hopes high up,” he said.

And when he stepped out after almost 23 long years, he thought to himself, “How do I begin really, really put my life back together?”

Garrett is now in Detroit, still enrolled in community college and close to his associate’s degree, and currently with his family and getting used to the fast-paced life again.

His favorite thing to do is driving at night, enjoying the small moments alone that he was never afforded in prison.

Want to support reporting like this? Consider making a gift to Michigan Radio today.