- Adobo Boy is located at 3740 28th Street Southeast, Kentwood, Michigan.

- Chef Jackie Marasigan's signature dishes are chicken adobo and pork adobo, both of which are staples in Philippine cuisine.

- Find the menu here.

There’s a family in West Michigan bringing all the flavors and fun of a Filipino house party to the Grand Rapids area. In the corner of their restaurant, Adobo Boy, you’ll find an essential part of nearly every Filipino living room: a karaoke machine.

“It's more fun at Adobo Boy, because when you come here, you have to sing or dance while waiting for your orders,” Jackie Marasigan, owner of the restaurant, said. Her quip is a parody of an old tourism marketing campaign slogan for the Philippines: “It’s more fun in the Philippines!”

While more Filipino eateries have popped up in recent years, especially in the southeast corner of Michigan, that’s been less true of the state’s west side.

That’s where Jackie and her family come in.

No-frills home cooking

The restaurant’s signature dish, adobo, is a staple of Filipino cuisine. Traditional Filipino adobo is a savory, marinated meat dish, typically made with chicken or pork. Jackie offers both, alternating the menu every week. The meat is marinated in vinegar, soy sauce, and garlic, and then braised.

Every household has a different adobo recipe. Jackie adds sugar to her marinade. Some folks like a lot of vinegar, some like more soy sauce, and some don’t use soy sauce at all. Some like to add a boiled egg or diced potatoes to the recipe. The variations are infinite.

The only real requirement, Jackie explained, is vinegar. Before refrigerators were widely accessible in the Philippines, vinegar was used as a preservative.

“It is a very common or iconic food in the Philippines, so each… province of the Philippines has its own version of adobo,” Jackie said. “Some use coconut milk, some are spicy, some are dried.”

Jackie’s recipe comes from Davao City, where she grew up watching her parents prepare meals for not just their family, but for the neighborhood.

“My dad, he would wake up at three a.m., four a.m., to prepare this… roasted pig,” Jackie recalled. “So his cousins, their relatives, are all there at three a.m., four a.m., just to cook. And then, I remember they had this big wok, the largest wok I’ve seen in my life. And then they’d cook there for the whole community, for free!”

The adobo she serves now combines her mother’s and father’s recipes, and she intends to keep it that way. Jackie’s not interested in offering Filipino-American fusion, but in sharing the no-frills home cooking she grew up with.

Founded on family

Adobo Boy’s namesake is in honor of Jackie’s son, Redd.

“So basically, when I was around three or four, my mom started feeding me adobo, and I fell immediately in love with it because of its taste,” Redd said. He is 10 years old, quiet, but not shy, and eager to help with the family business. “I always requested her, ‘Mom, can I have some adobo?’ So she nicknamed me The Adobo Boy, because I really love adobo!”

![[Pictured left to right] Ace, Jackie, and Redd Marasigan sing Lola Amour’s “Raining in Manila” together on Adobo Boy’s Karaoke machine.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/0dfc0ac/2147483647/strip/true/crop/5312x7968+0+0/resize/880x1320!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F00%2F8b%2Fc02890674cc7b8a33f1203e1e7fe%2Fkaraoke.jpg)

For many years, Jackie worked full-time as a nurse. Catering Filipino food was a side project that began with the Grand Rapids Asian-Pacific Festival — an annual event that was founded by her husband, Ace. The idea for a cultural festival materialized during a car ride with Redd sitting in the back seat.

“It's actually really a family affair,” Ace said of the festival. “Jackie and I… after attending another festival, we decided, ‘Hey, we need something that represents the Asian community.’ Something where Redd — because at that time, he was only two — we wanted him to see representation of himself.”

According to census data from 2020, Kent County residents of Asian descent make up just over 4% of the population. Filipinos are a subset of that slice. Attendance at the annual festival has offered encouragement that the local Asian community, though relatively small, is active and vibrant.

“It's been our eighth year for the [Grand Rapids Asian-Pacific Festival], and this last year, just in June, we saw a great influx of the younger generation coming out,” Ace said. “People are just feeling the representation, feeling the love, and feeling also… the collaboration that we’re trying to create.”

A haven far from home

Adobo Boy feels like an extension of the Grand Rapids Asian-Pacific Festival’s mission.

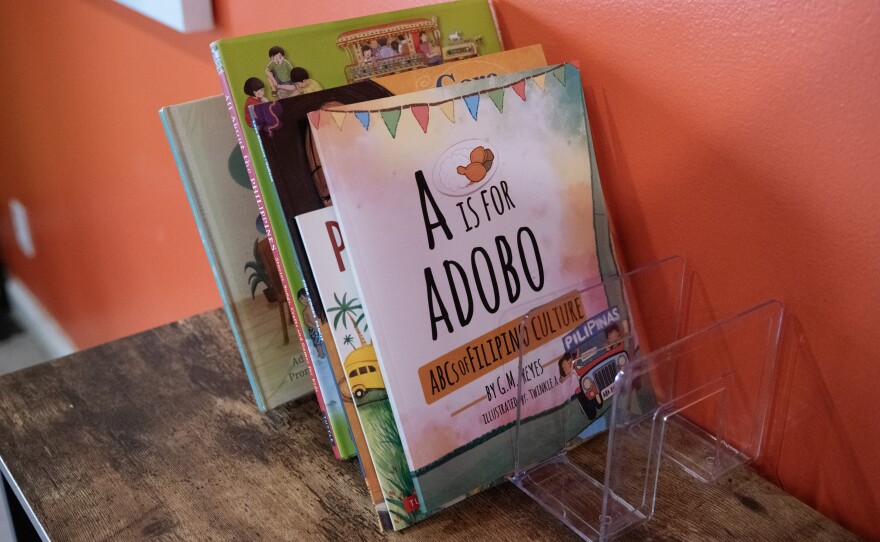

The restaurant shares a kitchen and dining room with two other restaurants: Amazing Myanmar Asian Cuisine, and Brunch and Rice, which serves Hmong, Laotian, and Thai food. Adobo Boy’s corner of the dining room features a humble karaoke machine, several children’s books featuring Filipino protagonists, and a mural of a Philippine city street. The central subject is a Jeepney, one of the most common forms of public transportation.

“It says, on the Jeepney, ‘Mabuhay!’ It’s a very welcome word from Filipinos. When you go to the Philippines, they would say, ‘Mabuhay!’ to every visitor that comes,” Jackie said.

The term is typically used in formal settings when addressing a group, and can carry multiple meanings, including, “to live.”

The Marasigans are excited to share their culture with a community that might know nothing about Filipino food. But the space is also a warm welcome for Filipinos familiar with the flavors, smells, and visual symbols of a home that’s far away.

“We've seen families bring their mom and dad from the nursing home… who came here to the United States when they were young, and be able to taste the food again. It brings back so much joy,” Ace said. “But you can see some of their faces — just lights up, smiles. We even had a family where the mom was teary-eyed, because the taste reminded her so much of home and family. And so what Jackie’s bringing to the community is something amazing. And for me, I’m so proud of her.”

The Dish is supported by the Michigan Arts and Culture Council.

![[Pictured left to right]: Ace, Redd, and Jackie Marasigan at the Adobo Boy counter.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/b03f9fa/2147483647/strip/true/crop/7957x4901+0+202/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F1b%2Ff2%2Fe89a490144db89f1717bbce0045c%2Fportrait-02.jpg)