Some wild stuff is about to go down in Michigan politics, and it all has to do with maps.

Normally, the maps that mark political districts get redrawn every 10 years.

But now there’s a good chance in Michigan the maps will get redrawn twice just in the next two years.

First, because of an order from a federal court. And then, in 2021 the maps will get redrawn, but with an entirely new process that voters approved last year. The maps could totally reshape Michigan politics, and then reshape them again only a year later.

There’s a chance the first redraw won’t happen. Right now it’s scheduled to go down by August 1. But that’s because of a federal court decision, and it’s still possible the U.S. Supreme Court will step in to stop it. The case is already on appeal.

One person who’d like to see that appeal succeed, and see the current maps stay, is this guy:

“I mean, I voted for ‘em, so yeah,” says Randy Richardville, who was the Republican leader of the state Senate in 2011 when the current political maps were drawn. The federal judges of the Eastern District of Michigan ruled that the maps Richardville and his colleagues approved were gerrymandered to “entrench Republicans in power.”

Richardville says he still believes they followed the rules. And he says he’s concerned about what comes next. Because it is a bit bonkers.

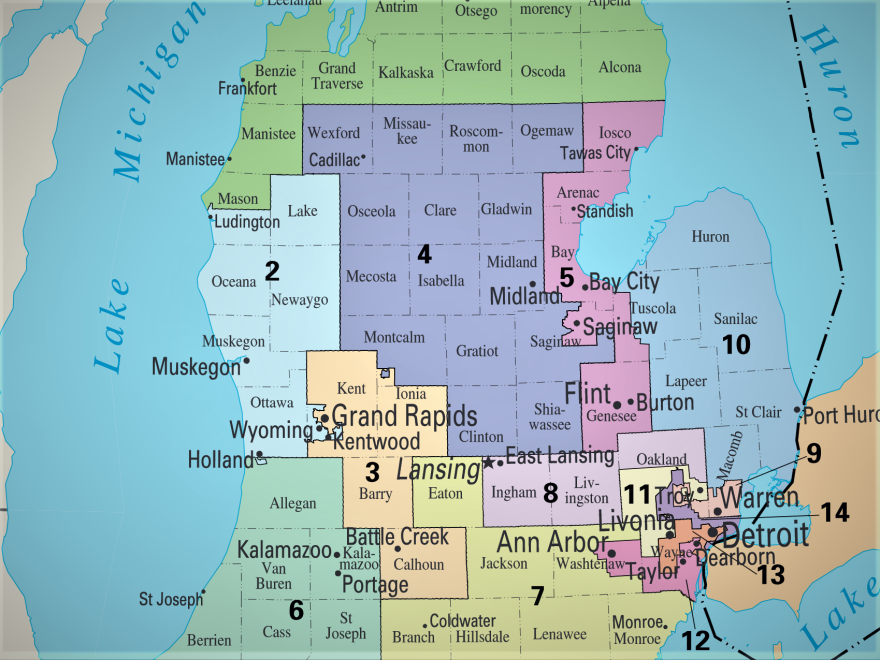

First, the state legislature and the governor have been ordered to redraw 27 political districts for U.S. Congress, the state House and the state Senate by no later than August 1.

If they don’t make the deadline, judges for the Eastern District of Michigan say the court will draw the maps.

"Yeah I think it is going to be kind of wild," says former Senate Majority leader Randy Richardville. "I think I'm glad I'm not up there right now."

And then next year, there will be a special election to put new people in the new districts.

And then the year after that, the new voter approved redistricting commission will kick into effect and redraw the maps all over again in time for the 2022 election.

For Lansing folks, it’ll be a wild ride.

“Yeah I think it is going to be kind of wild,” Richardville says. “I think I’m glad I’m not up there right now.”

Here’s the thing. The hard part about drawing these political maps is not the drawing part.

“There are plenty of mathematicians that would jump at the chance to present the legislature with maps that are not the maps that were drawn in 2011,” says Davia Downey, a professor of public administration at Grand Valley State University.

Maps can be drawn with software. You can come up with thousands of options with not a lot of effort.

Richard Leadbeater is with Esri, a company that makes some of the map drawing software. And it has some really detailed geographic data.

“Could you for example go in and draw political boundaries based on people’s consumer preferences, like one district you want to maximize for coffee lovers, another district for tea lovers, that sort of thing?” I ask him.

“Absolutely,” he says. “The concept’s the same. It’s what Starbucks does.”

“And the data is there for political redistricting too?”

“Yes, oh very much so.”

So the maps can be made however you want to make them.

"If I came up to you and said make a map and you get to keep your job, wouldn't you make a map?" says Richard Leadbeater of Esri, a company that makes redistricting software.

The problem is deciding exactly which version of the map is best. And Leadbeater says if you’re a politician, there’s an easy way to decide.

“If I came up to you and said make a map and you get to keep your job, wouldn’t you make a map?” he asks.

Yes, right? We’d all make whatever map helped us.

And that is one of the big reasons why voters in Michigan decided they don’t want politicians to draw the lines anymore.

So, starting in 2021, there will be a new process. Michigan will have an independent commission to draw the maps, and to hold public hearings.

What the commission decides is important is totally unknown right now. It could be very messy, could be very contentious. And some people think it won’t be any better than the old process.

But GVSU political science professor Davia Downey is optimistic. She also serves on the board of Voters Not Politicians, the organization that led the ballot drive to create the new redistricting process in Michigan. Downey says, no matter how it shakes out, there will be a lot more people engaged in the map making process.

“There’s going to be a lot more discourse about map drawing and about representation and about what lines mean,” Downey says, “because people are now aware that lines actually matter and they matter tremendously. And so I’m excited to see what happens.”

If you want to be one of the people drawing the maps, you can apply to be on the commission for the 2021 redistricting. The state will start accepting applications later this year.

This post has been corrected to reflect that Davia Downey is a professor of public administration, not political science.