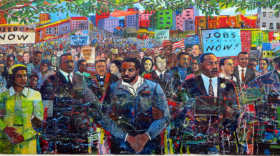

It's been an historical election year shaped by an ongoing pandemic, as well as a summer surge of protests against police brutality and racial injustice. Many politicians and activists—Democrat and Republican alike—urged voters to cast their ballots with events of the past months in mind. Here's a piece of Michigan history that offers some insight on how civil rights movements can affect elections.

[Get Stateside on your phone: subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Podcasts today.]

The presidential election of 1968, which pitted Richard Nixon against Hubert Humphrey, came one year after massive civil unrest in Detroit in the summer of 1967. To learn more about how the Detroit uprising and the civil rights movement affected the presidential, state, and local elections of 1968, Stateside spoke with Ken Coleman. He’s a journalist for Michigan Advance and the author of On This Day: African-American Life in Detroit.

Detroit’s political landscape in ‘67 and ‘68

Coleman says many African Americans in Detroit held significant mistrust toward the city’s government and police, especially after the 1967 uprising.

“What Detroit looked like in 1968, even coming off the rebellion year of 1967, was still a city where elected leadership was largely lily white,” he said. “While there had been a sprinkle of African Americans who had been elected throughout the 1960s, the city, in the eyes of Blacks and perhaps other minorities too, was not a city government that was representative of them, and it didn't look like them.”

“Law and order”

While conflict over the Vietnam War played a significant role during the 1968 election year, the issue of law and order at home in the U.S. was a deciding factor in the presidential contest, Coleman says.

“A response to what some folk, like Richard Nixon, thought was upheaval going on in America, the uprising by African Americans in major cities like Detroit, Cleveland, Los Angeles, and New York,” he said. “But also a visceral, violent response against the summer of love in 1967 and counterculture politics—Nixon, even during his presidency, sort of pushing back against the hippies, whites and others, who were fighting against the Vietnam War. But also a feeling that the civil rights movement was moving too far to the left, and moving too fast for America.”

Shifts in city leadership

The number of Black leaders in Detroit began to increase amid the 1960s civil rights movement and after the 1967 uprising. Detroit voters elected Coleman Young, the city’s first Black mayor, in 1973.

“For the first time, African Americans begin to have a comfort level and a confidence in the force that oversees and polices the city, because you have an African American mayor who appoints people, who appoints what is still a majority white police force but in successive years becomes more African American. That is a development that has its roots in 1967 rebellion politics and in 1968 Michigan presidential politics,” Coleman said.

Parallels between 1968 and 2020

But in 2020, there are still many echoes of '67 and ‘68, and a new generation of activists in Detroit is still protesting police brutality toward Black Americans. Coleman says civil rights movements of today share patterns with the late 1960s, like high-profile shootings and presidential politics, as well as civil unrest and how local and state law enforcement and officials respond to it.

“History is a set of events that builds on itself. And movements are created, they change over time, they may languish at times but become reinvigorated. The sort of striking similarity between 1968 and what we’ve seen in 2020 thus far is the real similarity in the study and this look at how America polices communities, and the reaction on both sides to how that’s being carried out.”

Coleman covered the rallies that were held in Detroit this summer after the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota, and he says he noticed some conversations going on among today’s young activists and those who worked in the city during the late 1960s.

“In interviewing people from both generations, [I] realized that there was a lot of commonality. And some things had changed, obviously,” he said. “But there was still a disconnect and a divide between everyday people and the law enforcement agency that polices that neighborhood or that community.”

Listen to the full conversation above.

This post was written by Stateside production assistant Nell Ovitt.

[For more Michigan news right on your phone, subscribe to the Stateside podcast on Apple Podcasts or Google Podcasts today]

Want to support reporting like this? Consider making a gift to Michigan Radio today.