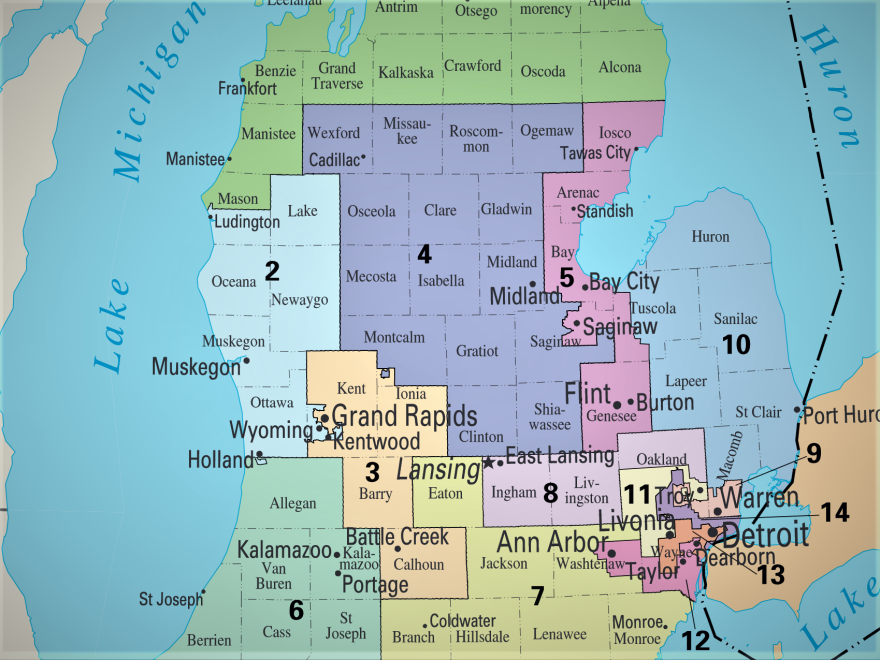

Michigan’s new Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission, which was approved by voters in 2018, is continuing its work of drawing new congressional and legislative districts for the state. In recent weeks, the commission has encountered some challenges related to timing and funding, especially as 2020 Census data needed for the process won’t be available until July. As the group continues meeting virtually — which members of the public are encouraged to get involved in — Stateside took a look at the history of the representation Michigan has now, and why there’s been a movement to change the state’s legislative map.[Get Stateside on your phone: subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Podcasts today.]

John Lindstrom, the former publisher of Gongwer News Service and a retired journalist covering state capital politics, says that one factor legislators can consider when drawing district boundaries is population in a particular area. But another factor is land, which has historically played a big part in the creation of district lines.

“All four of Michigan's constitutions, going back to 1835, make a specific reference to how you apportion on the basis of county boundaries or local boundaries,” Lindstrom said.

The question of how to draw legislative boundaries — and what information should be used to establish them — has been complicated for a long time. It came before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1962 when, in Baker v. Carr, the court ruled that it had the power to get involved with state redistricting plans, Lindstrom explains.

Michigan’s current constitution was ratified the following year, in 1963. Lindstrom says that the constitutional convention’s meetings at the time “went swimmingly” — until the discussion turned to the divisive issue of redistricting.

“Then it all fell apart,” he said. “The Democrats wanted a one man, one vote situation. And the Republicans wanted a situation that would still involve a formula that looked at, for one thing, land, territory, boundaries, and population.”

Lindstrom says that in 1982, the Michigan Supreme Court paved the way for everyday citizens, rather than politicians, to create a redistricting plan themselves. But that didn’t happen right away.

“So that left it up to the legislature,” Lindstrom said. “For the last three redistricting cycles, it has been largely a Republican-controlled state government. And so they were the ones crafting the lines.”

But new maps are coming. The group Voters Not Politicians led the movement for the Independent Redistricting Commission Initiative (Proposal 2), which Michigan voters passed in 2018. The proposal created a new, independent redistricting commission made up of citizens, not legislators or special interest groups. They’ll be drawing district lines with communities of interest in mind.

Lindstrom says there isn’t yet a strict definition of what a “community of interest” might be, and that the commission members could be considering a variety of groups as they decide where to create new district boundaries.

“You think, first of all, to, okay, protecting minority populations,” he said. “But you can get into all kinds of different things. You know, are you talking about a specifically rural area, heavily agricultural? Are you talking about a specifically industrial area where you’ve got a lot of union workers? Are you talking about an area, for example, say, Oak Park, where you have a very heavy Jewish population, as well as a very heavy Muslim population, or Dearborn, where you have a very heavy Muslim population?”

Lindstrom says he thinks it’s possible that the citizens commission’s decisions could later be challenged, particularly if one political party doesn’t like the results. But, he adds, he sees the statewide success of Proposal 2 as a sign that a majority of Michigan voters are interested in a nonpartisan approach to redistricting. Lindstrom says he told Voters Not Politicians as much when they polled him about their work.

“I said, well, you had no money, really, until close to the end of the campaign. You did it all on a citizen organization, which almost never happens these days. You didn't pay for petition signatures, which almost doesn't happen these days. You were able to put together a proposal that people agreed with, and you won a majority of the voters in this state — and not only a majority of all the voters, probably a majority of both parties. And that's just not supposed to happen,” he said.

This post was written by Stateside production assistant Nell Ovitt.